Only a military hospital can really show you what war is.

—Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front

Much of the original hospital still stands. It has undergone several additions over the years and is now populated by the Science Department of Edinburgh Napir University. Nevertheless, the old residents of the Craiglockhart War Hospital for Neurasthenic Officers continue to exert their presence, largely through the War Poets Collection, a small exhibition that occupies the original atrium of the building. Black and white photographs line the walls and grainy film footage of the trenches plays on video monitors. Visitors are invited to study the affable features of Wilfred Owen and his flinty-looking hero, Siegfried Sassoon. Books of their poetry—and the dozens of subsequent biographies and academic treatises—fill the bookcases.

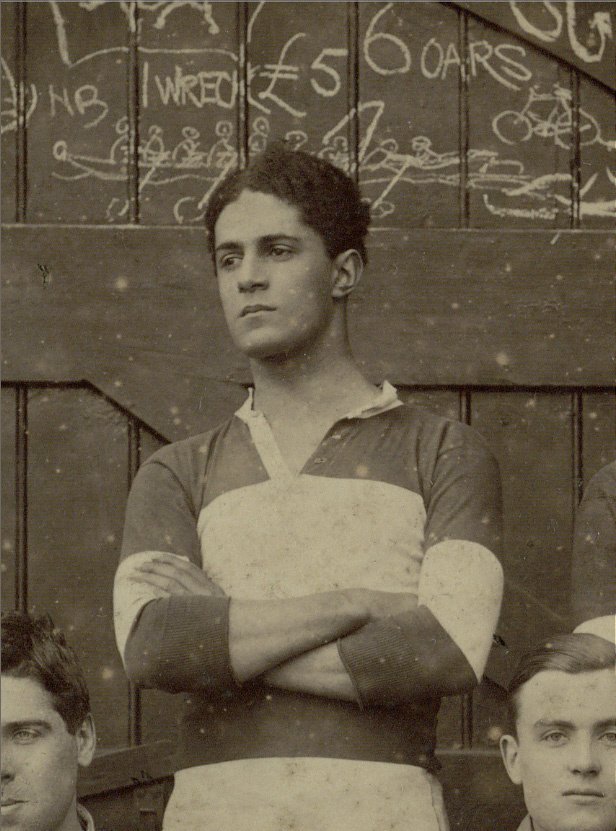

Lesser-known figures are commemorated in the collection, too, including David Louis Clemetson, the 20-year-old law student from Cambridge, who became the highest-ranking Black officer in the British Army at the time. Despite the 1914 Manual of Military Law, which restricted non-white soldiers from assuming command positions, Clemetson was promoted to Lieutenant in October 1915. He also spent time at Craiglockhart, having been diagnosed with “neurotic depression” and “stress of service.”

The debilitating symptoms of what came to be known as "shell shock" could include temporary blindness, loss of speech, paralysis, uncontrollable tremors, hallucinations, memory loss, disturbances of gait, and recurring nightmares. Some of these symptoms were preserved on film by Dr. Arthur Hurst at Seale Hayne Hospital in Devon, England.

David Louis Clemetson, detail of photograph to the right.

The First The First Trinity and Fifth Boat (also known as the “Rugger Boat”) team that rowed in the Lent Bumps, February 1914. Courtesy of the Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge, Cambridge University.

The forms of treatment for shell shock varied, but doctors on both sides of the conflict experimented with Sigmund Freud's new method of "talk therapy." One of the most prominent of these was the noted anthropologist and psychiatrist, William Halse Rivers. At the outbreak of the war, Rivers signed up to serve as a civilian physician at the Maghull Military Hospital near Liverpool, where doctors were experimenting with techniques such as dream interpretation and hypnosis.

W. H. R. Rivers, Painting by Douglas Gordon Shields, Courtesy of St John's College, University of Cambridge

When Rivers was transferred to Craiglockhart, he began to formulate his own theories regarding the origin and treatment of the "war neuroses." In contrast to Freud's emphasis on sexual conflict, Rivers emphasized what he called the "self-preservation instinct." He published several important works on the topic, including "On the Repression of War Experience," (1917), "Psychiatry and the War" (1919), and Conflict and Dream (1923), which contributed to a larger body of work that revolutionized the British perspective of mental illness and its treatment.

British novelist, Pat Barker, dramatized life at Craiglockhart Hospital in her 1991 book Regeneration. Drawing extensively on first person narratives from the period, Barker created characters based on historical figures who were patients or who worked at the hospital. The novel portrays the compassionate nature of the psychotherapeutic approach in contrast to the "faradization" (or electric shock) treatment that was being conducted in several other hospitals during the period, most notably by Dr. Lewis Yealland, who, by his own account, forced soldiers back into service through excruciatingly brutal means.

Pat Barker's novel was brought to the stage in 2014 to mark the Centenary of the First World War. The novel was also adapted for film in 1997.

Lieutenant John Warwick Brooke, 9th Cameronians (Scottish rifles) daylight raiding party near Arras, France, 24 March 1917. Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

“Do they matter? —those dreams from the pit?...”

Siegfried Sassoon: the University of Cambridge has digitized a collection of Sassoon's war diaries.

Several of the soldier-poets being treated at Craiglockhart wrote about their dream-life in shockingly realistic terms, which was in stark contrast both to the public perception of war at the time and to the confidently patriotic verse of earlier war poets. In his book, The Poetry of Shell Shock, Daniel Hipp argues that this new kind of poetry provided soldiers the means to express the inexpressible experience of the war, and in turn, a means to heal from their traumas.

In "Does It Matter" (1918), Siegfried Sassoon—who was being attended by Dr. Rivers at Craiglockhart—specifically drew attention to the significance of soldiers' traumatic dreams. The questions he poses remain all-too-timely today, as many contemporary military administrations struggle to respond to the epidemic of suicide among veterans.

Does it Matter?

DOES it matter?—losing your legs?...

For people will always be kind,

And you need not show that you mind

When the others come in after hunting

To gobble their muffins and eggs.

Does it matter?—losing your sight?...

There’s such splendid work for the blind;

And people will always be kind,

As you sit on the terrace remembering

And turning your face to the light.Do they matter?—those dreams from the pit?...

You can drink and forget and be glad,

And people won’t say that you’re mad;

For they’ll know you’ve fought for your country

And no one will worry a bit.

2nd Lieutenant Wilfred Owen provided one of the more sustained descriptions of the nightmares that tormented him in "Dulce Et Decorum Est." The poem was published posthumously in 1920; Owen returned to the Front after his treatment at Craiglockhart and was killed in action just one week before the armistice.

Portrait of Wilfred Owen. Copyright the English Faculty Library, University of Oxford and The Wilfred Owen Literary Estate.

After the war, the doctor that had treated Owen at Craiglockhart, Arthur Brock, wrote about the treatment of shell shock in a book called Health and Conduct. While Brock refrains from revealing that he treated Owen (observing the decorum of doctor-patient confidentiality), he does describe the importance of articulating one's dreams: “In the powerful war-poems of Wilfred Owen we read the heroic testimony of one who having in the most literal sense ‘faced the phantoms of the mind’ had all but laid them ere the last call came; they still appear in his poetry but he fears them no longer.”

Dulce Et Decorum Est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Sharon Sliwinski is the creator and editor of The Museum of Dreams and professor of Information and Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario in Canada.

"Treating Shell Shock" © February 2017