Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, begins with the story of his childhood. Places and names are significant to this narrative. At his birth, Mandela was given the name Rolihlahla (“pulling the branches off the tree,” read: “troublemaker”). When he was sent away to school at age seven, he acquired a clan name, Madiba, and his first teacher, in accordance with colonial custom, gave him a Christian name, Nelson. After a rebellious youth, Mandela eventually made his way to the University of the Witwatersrand, where he slowly worked toward a degree (repeatedly failing his qualifying exams) as the only black law student.

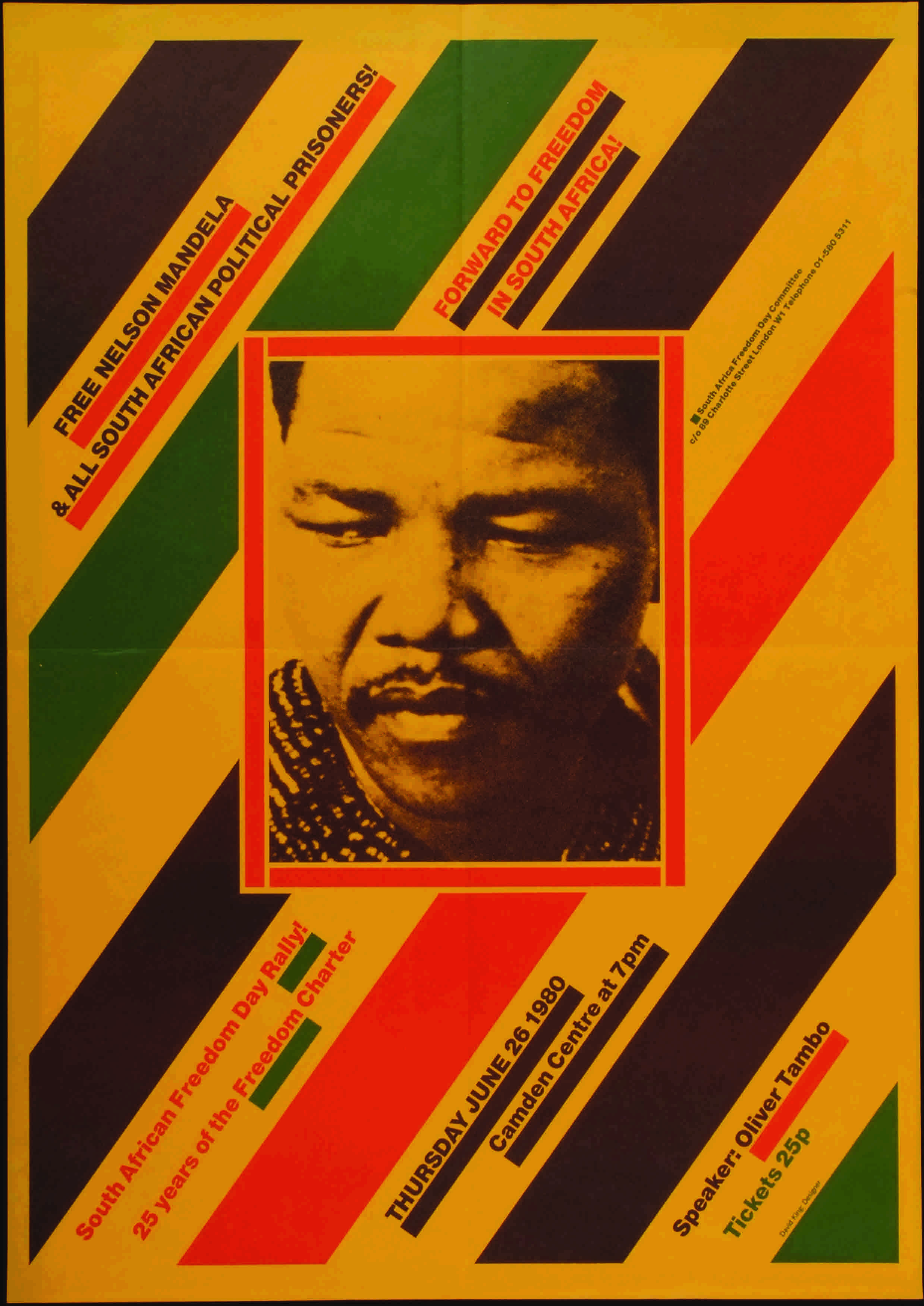

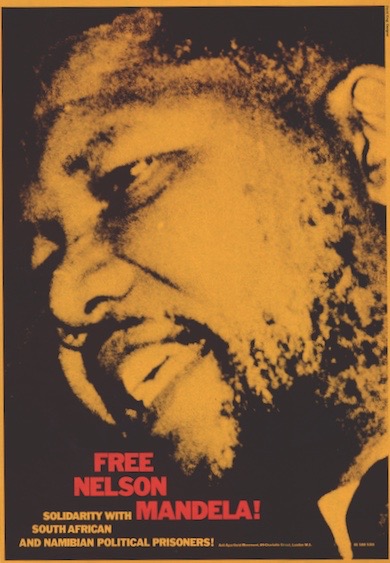

As a young lawyer practicing in Johannesburg in the 1940s, he joined the African National Congress (ANC) Party. In 1951, after the National Party took power, he helped organize the Defiance Campaign in response to the new apartheid laws. When the ANC’s nonviolent tactics were met with violent reprisals from the Afrikaner government, Mandela began advocating for a different strategy. In 1961, he publicly stated, “If the government reaction is to crush by naked force our non-violent struggle, we will have to reconsider our tactics.” The young leader suffered a series of bans, served several jail sentences, and eventually cofounded the militant wing of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe(or MK). He went underground and undertook guerrilla warfare training, but was eventually captured and tried at the infamous Rivonia Trial, in which he and seven other ANC members were found guilty of a series of charges related to sabotage. Narrowly escaping the death penalty, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison on June 12, 1964. He did not see freedom again for twenty-seven years. When he was released on February 11, 1990, he went on to lead the transitional government and became the first democratically elected president of South Africa, serving just one term, from 1994 to 1999.

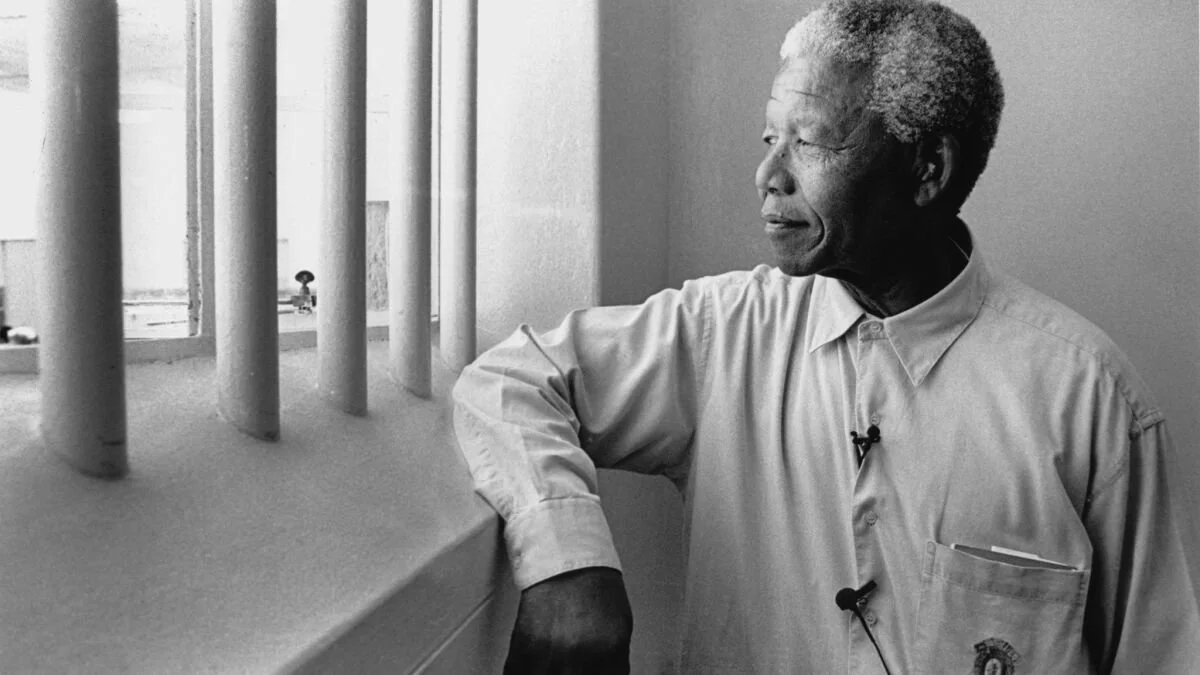

One of the most harrowing sections of Mandela's autobiography is called “The Dark Years.” The section’s title refers to the years he spent imprisoned on Robben Island. It reads like a training manual for surviving dark times. Madiba describes the various hardships imposed at the newly designed prison: a discriminatory dress code and segregated diet that the National Party created for each of the four racial classes they invented, brutal forced labour at the island’s lime quarry, and harsh restrictions on visitors and letters (one visitor and one letter were permitted every six months, always censored, often denied altogether). There is a sparse account of Mandela’s devastation at the news his mother’s death in 1968. This grief was deepened less than a year later when he received a telegram informing him of his eldest son’s death as a result of injuries sustained in a car crash. Each of these experiences imposed a distinct psychological pressure: “The challenge for every prisoner, particularly every political prisoner,” Mandela counsels, “is how to survive prison intact, how to emerge from prison undiminished, how to conserve and even replenish one’s beliefs.”

Amongst these soul-rending accounts, Mandela relays one of his nightmares to his readers, which, he reports, returned repeatedly to haunt him during his twenty-seven-year imprisonment:

I had one recurring nightmare. In the dream, I had just been released from prison—only it was not Robben Island, but a jail in Johannesburg. I walked outside the gates into the city and found no one there to meet me. In fact, there was no one there at all, no people, no cars, no taxis. I would then set out on foot toward Soweto. I walked for many hours before arriving in Orlando West, and then turned the corner toward 8115. Finally, I would see my home, but it turned out to be empty, a ghost house, with all the doors and windows open, but no one at all there.

The astonishing passage seems just as dramatic as Mandela's famous speech from the Rivonia Trial in which he named apartheid’s injustice and defined the ideal for which he was prepared to die: a democratic and free society. The nightmare seems to attest something similarly poignant about the leader's experience of prison, offering both a private account of his emotional state and a profound testimony about the political conditions of his unfreedom.

As Sigmund Freud taught us, dreaming is a distinct species of thinking. In The Interpretation of Dreams, her wrote: “At bottom, dreams are nothing more than particular form of thinking made possible by the condition of the state of sleep.” Dreams think, Freud insists, even as this psychological activity bears little affinity to the more familiar forms of conscious reasoning.

More precisely, Freud proposed that a dreamer experiences her thoughts rather than “thinks” them in concepts. Dreams dramatize an idea, constructing a situation out of thoughts that have been transposed into images. While the particular scenes and actions of dream-life might seem utterly alien to waking-thought, they nevertheless arise out of incidents of our lived experience. Dream-life is anchored in the material world, tethered to the particular conflicts and conditions of the dreamer’s social situation.

Defendants Moses Kotane and Nelson Mandela leave a courtroom in Pretoria, South Africa, during the Treason Trial. January 1, 1958. Photograph (above as well as the title image) courtesy of Jurgen Schadeberg

“That night I returned with Winnie to No. 8115 in Orlando West. It was only then that I knew in my heart I had left prison. For me No. 8115 was the centre point of my world, the place marked with an X in my mental geography." Nelson Mandela, from The Long Walk to Freedom.

The various locations mentioned in Mandela’s dream can certainly be traced back to sites of his lived experience: the jail in Johannesburg where he spent time as an awaiting-trial prisoner in 1962 prior to the Rivonia Trial, but also the first home he owned, the little red brick house, number 8115 in Orlando West, a place Mandela once called the “center point” of his world, “the place marked with an X in my mental geography.” This modest building has subsequently taken on another layer of significance since 1999 when it was rebuilt and transformed into a museum that now receives thousands of visitors each year. The nightmare also manages to index the tiny cell on Robben Island in which Mandela spent the majority of his sentence, albeit only through a negation: the dream-prison “was not Robben Island,” he insists. Such cancellations are a tell tale sign of repression, a signal that something is being withheld from consciousness because of the pain that would come with its acknowledgement.

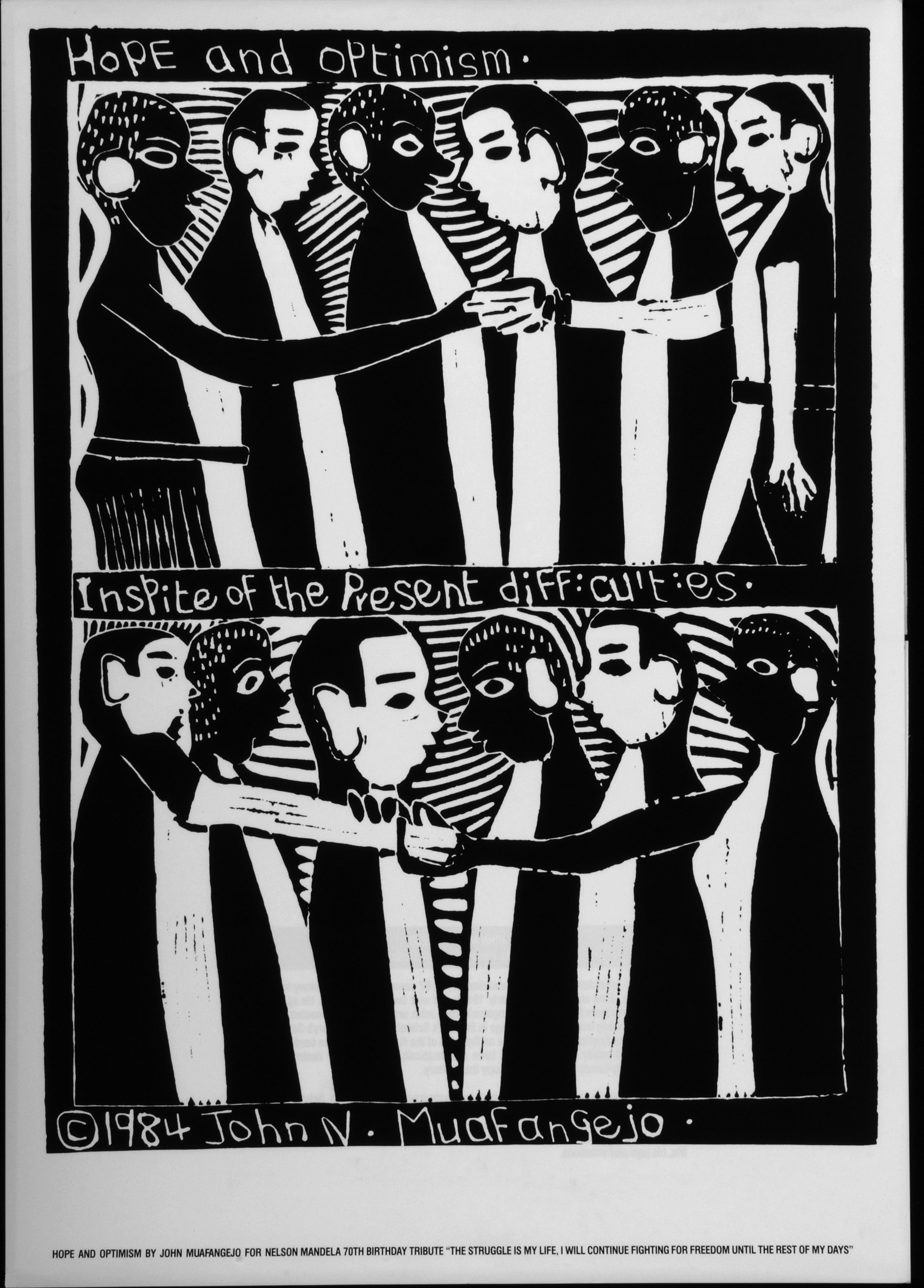

While dream-life relies on elements of the dreamer’s storehouse of experience to weave its landscapes, this is undoubtedly a queer kind of thinking. Dream-life is not a documentary presentation of events but rather a symbolic account of the dreamer’s lived experience. In Mandela’s case, his dream visually staged the sense of alienation and unfreedom that the prolonged incarceration inflicted: freedom to wander in an empty, uninhabited world is, of course, no freedom at all. Far from being a straightforward fantasy of escape, the nightmare achingly dramatized what a life separated from one’s loved ones felt like for the dreamer. It also testified to the experience of being ostracized from the larger political community of humanity, showing what it means to be denied that primary dimension of the human condition that involves belonging to a shared gaze—to see and to be seen to exist.

In the nightmare, Johannesburg was devoid of all people, all cars, and Mandela’s beloved home was turned into a ghost house. This empty landscape seems to symbolically figure the emotional experience of being banned from society. Spending a great portion of his life imprisoned felt akin to a world emptied of all human presence. The nightmare gave visual form to the violence that incarceration enacts, and more specifically, the violence that apartheid enacted: it figuratively conveyed the pain of depriving a human being access to the human world. More evocative than any declaration, Mandela's nightmare made manifest the way apartheid transformed the world into a ghost town.

Eli Weinberg, Crowd near the Drill Hall on the opening day of the Treason Trial, December 19, 1956. Courtesy of Museum Africa, Johannesburg.

Sharon Sliwinski is the director of The Museum of Dreams and professor of Information and Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario in Canada.

"The Prisoner's Nightmare" is an excerpt from Mandela's Dark Years (University of Minnesota Press, 2016) which is freely available on Manifold, an open-source platform.