In the way a dream comes to us at night, feelings come to me, and then I must rush to put them down. But these fantasies have to be given physical form, so you build a house around them, and the house is what you call a story, and the painting of the house is the bookmaking. But essentially it’s a dream, or it’s a fantasy.

—Maurice Sendak, Questions to an Artist Who is Also an Author

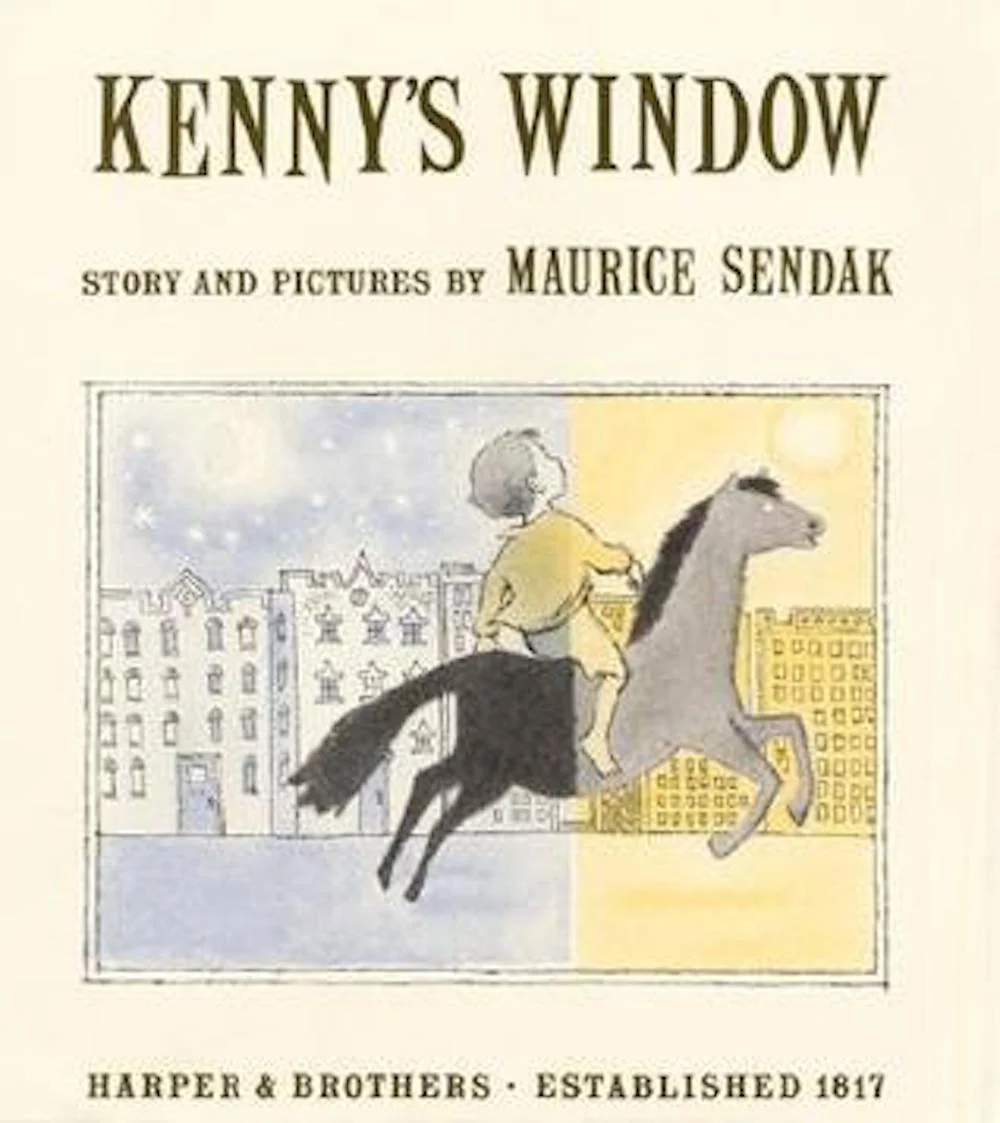

Storybooks fill the transition between our waking and sleeping hours, but it is hard to say what, exactly, their stories and pictures offer to the plots of our dreams. The reverse formulation—moving from dreamtime feelings to the material of the storybook—seems like a clearer path. In Maurice Sendak’s first storybook, Kenny’s Window, we find just such a dream to follow. Published in 1956 as a fictionalized illustration of one boy’s wishes, and inspired by a therapeutic case study, this storybook provides a striking depiction of the questions that a dream can arouse.

Sendak’s first book is concerned with the idea that dream-thoughts may need a place to call home. This can take time and call for creative work—alike to finding a form for a story in a book or to searching for resonance in the hearts and minds of an audience. Yet this story also represents a rather straightforward beginning to Sendak’s now famous explorations of the child’s fantasy life.

Kenny’s Window depicts a sequence of fantasies kindred to Where The Wild Things Are, In The Night Kitchen, and Outside Over There—picture books that later brought Sendak’s art and words into the bedtime rituals of millions of children. However, unlike its more fantastically ambiguous siblings, Kenny’s Window directly depicts a dream both in name and form. All this is to say Kenny’s Window is about more than a lonely boy and his captivating questions: the book lays out a young boy’s dream within its first pages and by the time we have reached the back cover readers have explored the lessons of dream interpretation.

Even before authoring his first book, the young illustrator experimented with drawings of unseen emotions and the imaginative preoccupations of the child’s world in his collaborations with writer Ruth Krauss. Kenny’s Window presents the next phase of these explorations. In this book we find both a dream and the start of a new approach to the picture book that zooms in on the child’s inner world. This innovative approach was in step with a larger shift in the genre of children’s literature which turned away from formulaic depictions of behavioural lessons and towards the frustrations of childhood depicted from the child’s view. Ursula Nordstrom, Sendak’s formidable publisher, often defended these innovations by saying that rather than publishing “bad books for good children,” she was in the business of publishing “good books for bad children.”

Kenny’s Window offers a glimpse of the postwar era of children’s book publishing. This was a time of expansion and experimentation for editors, authors, and illustrators, and a time when young Maurice Sendak was still an apprentice starting out in the profession. The book presents a view of the era’s thinking about dreaming and storybooks, but it also speaks to some of the tensions animating Sendak’s new approach. Depicting a dream seemed to offer Sendak an easy point of access to the child’s fantasy life—dreaming provides a playground for the imagination but interpreting a dream also provides a way to connect the narratives of childhood to larger psychological questions. Dream-feelings are given physical form in this storybook through illustrations, but what kind of introduction does a dream require? And, what else can be introduced through the animations of the child’s dream life.

The book opens with the protagonist awakening mid-dream. Kenny remembers a garden with a train. The garden has two parts: one side is cloaked in the darkness of night and the other bathed in the brightness of day. Kenny is enchanted by the possibility of living in a garden where he might spend days counting stars and while away his nights playing in the sun without ever having to sleep. The dreamscape promises comfort to a boy who is of two minds. But Kenny does not quite escape the demands of nighttime thoughts. Soon a rooster with four legs arrives on the train, bringing Kenny seven questions that he must answer:

Can you draw a picture on the blackboard when somebody doesn’t want you to?

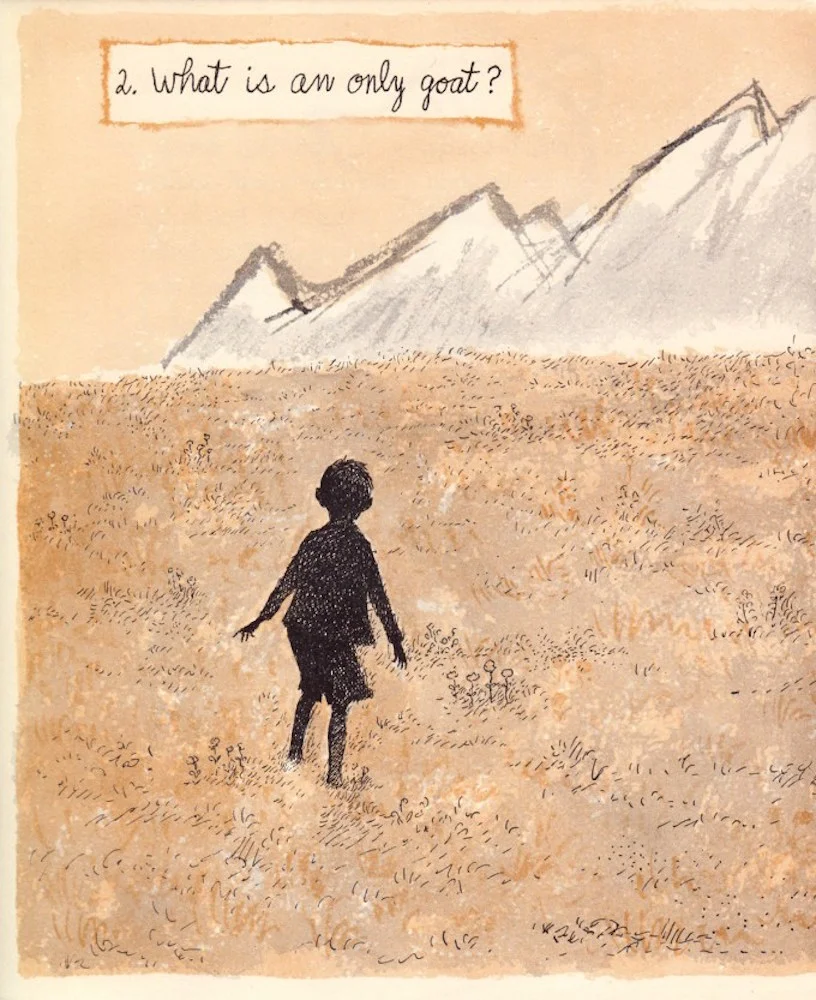

What is an only goat?

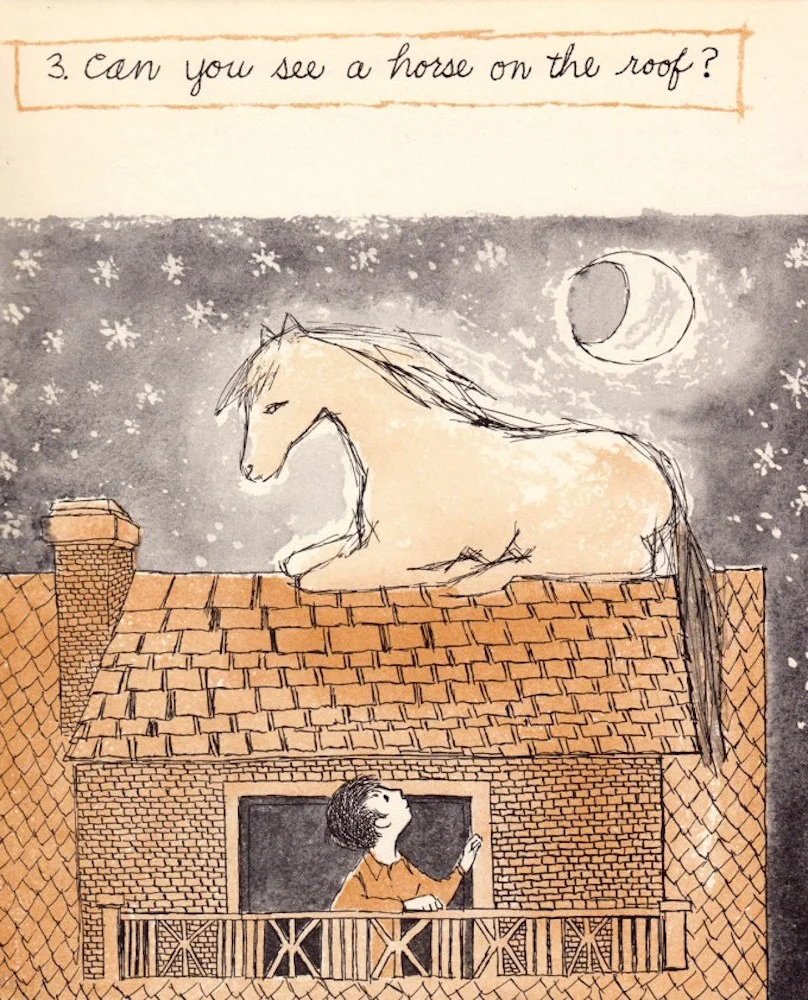

Can you see a horse on the roof?

Can you fix a broken promise?

What is a very narrow escape?

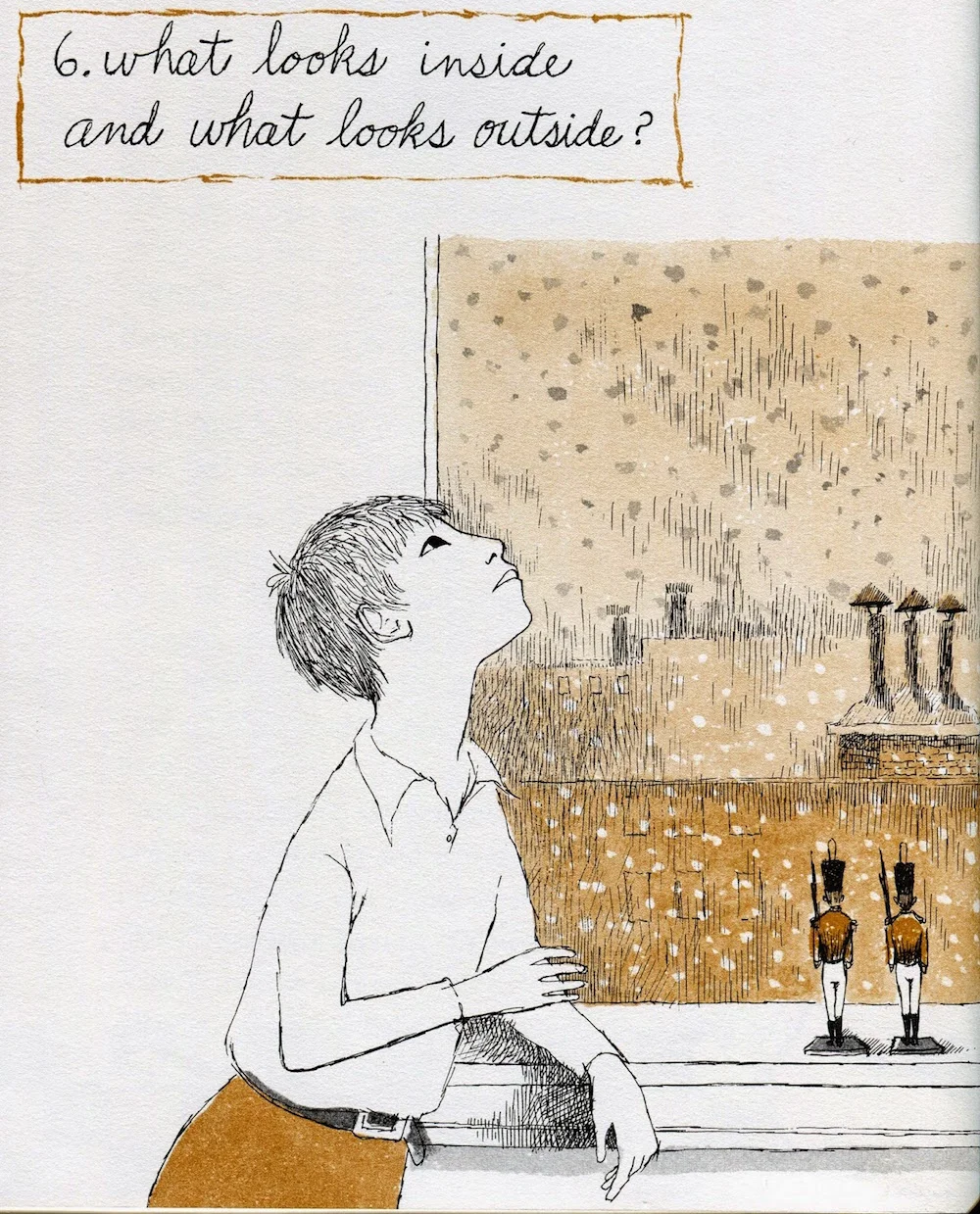

What looks inside and what looks outside?

Do you always want what you think you want?

Kenny wants to know if he can stay in the garden if he answers all the questions but he awakens before he learns if his wish will be fulfilled. The questions become tests and trials—explorations of the ways love can demand compliance, furnish loneliness, call for “good” behaviour that curtails the imagination, suffocate through the fear of its loss, obstruct the only routes traveling inwards or out, and make it terribly difficult to communicate our most basic needs and wants.

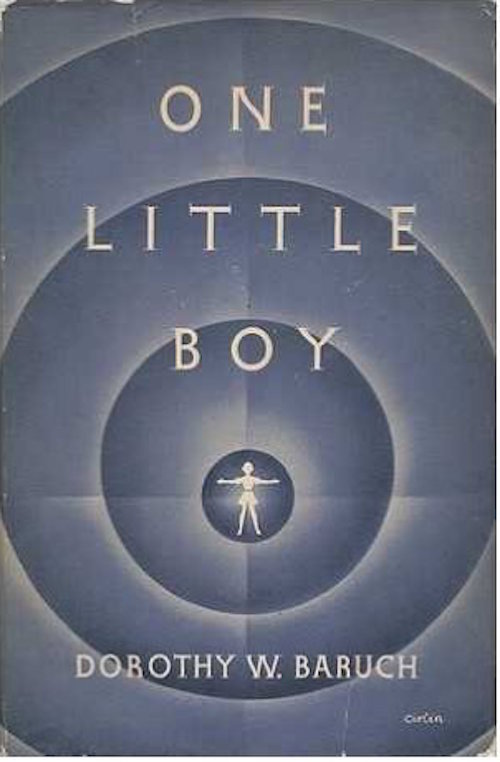

The dream, it turns out, makes use of things already experienced. To write Kenny’s Window Sendak looked to the early experiences of a seven-year-old boy named Kenneth. The story borrows from a psychoanalytic case study published in 1952 by Dorothy Baruch called One Little Boy, which chronicles the therapeutic treatment of a boy named Kenneth. Sendak’s interpretation moves away from the specificities of family life and the unique dramas of Kenneth’s situation recounted in Baruch’s case study. Instead, the children’s book invites us to explore the kinds of questions that might be asked of oneself through fantasies of the dreamworld. The context that could help us to understand Kenny’s situation and why he might need to seek answers to these questions is missing from Sendak’s book. Yet the absence of this explanation does not diminish the story. Instead Sendak presides over a rich exploration of one boy’s loneliness without making the source of that loneliness part of the story. The context he substitutes is Kenny’s dream.

Kenny’s seven explorations are richer for their associations with the case material—the deep pains and play of reparation of one little boy. And this, Sendak has said, is what drew him to the case. On the recommendation of his analyst Sendak read Baruch’s One Little Boy. The case resonated. As Barbara Bader has suggested, we might go so far as to imagine Baruch’s book as if it were written for Sendak. The author himself described his response to the case this way: “I was blindsided by that kid, by his inability to communicate. Kenny’s troubles suggested my childhood to me. I had been that lonely."

Conveying this experience of loneliness, Sendak tells a story of childhood companionship through Kenny’s imaginative explorations with Baby the dog, Bucky the teddy bear, and two toy soldiers. These relationships resonate with the value Sendak holds for the books and toys that animated his childhood. In an interview from 1966, Sendak admits:

I can still remember the smell and feel of the bindings.... I didn’t read them for a long time. It felt so good just having them. They seemed alive to me, and so did many other inanimate objects I was fond of. All children have these intense feelings about certain dolls or toys. In my case, this kind of relationship, if you can call it that, was heightened because up to the age of six I spent a lot of time in bed with a series of illnesses. Being alone much of the time, I developed friendships with objects. To this day, in my parents’ home there are certain toys that I played with as a child, and when I visit my parents, I’m also visiting those toys.

Distilled in the material of Kenny’s dream are associations to another history made from Sendak’s own memories. One benefit to looking at the case study and storybook side-by-side is to observe the way Sendak treated the case as the source material for Kenny’s unconscious conflicts—adding depth and layers of condensation to the dream fiction.

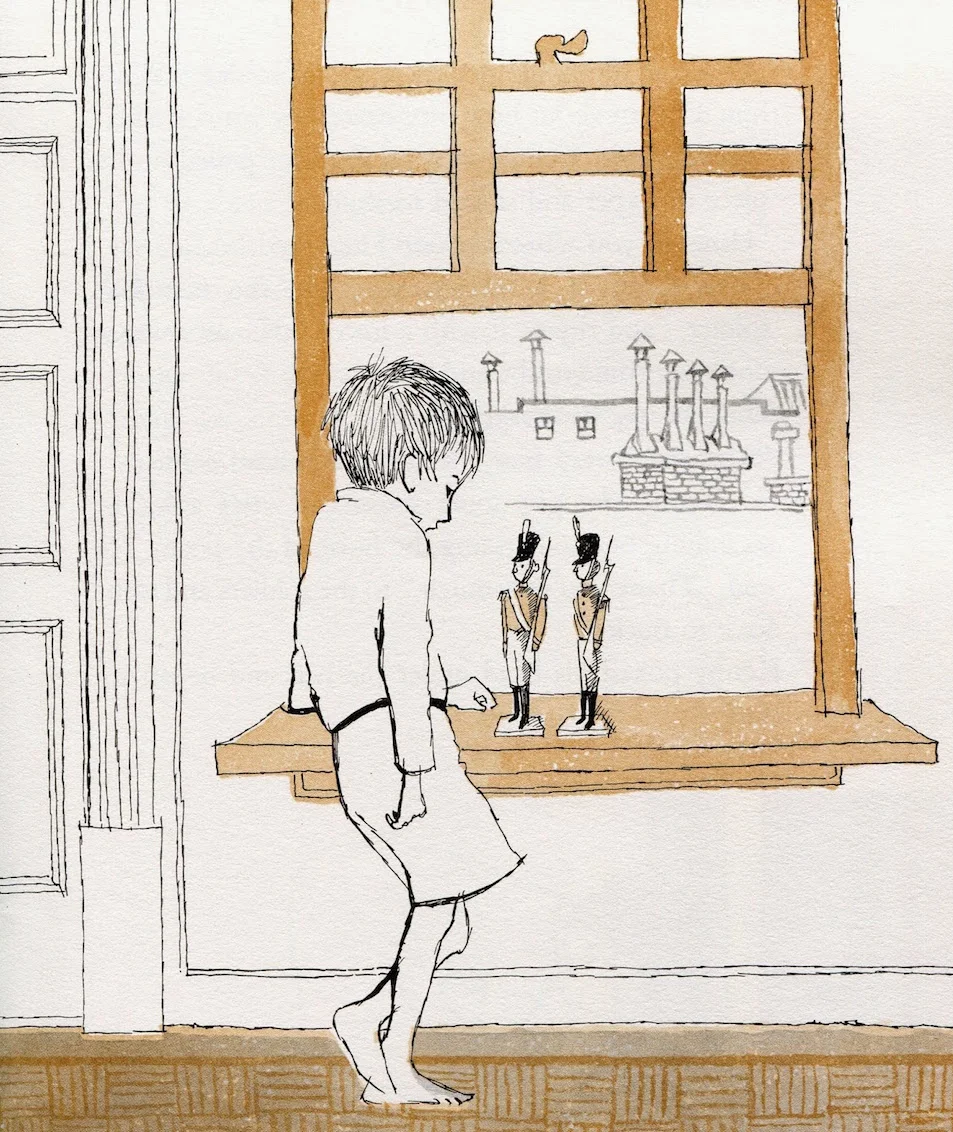

Two of the questions Kenny must answer are played out in heartfelt dramas with his toys. These objects are supporting characters and the constant companions of Kenny’s bedroom. The first question is taken up after Kenny’s teddy is left under the bed all night. He is hurt and lashes out in protest when Kenny writes on the chalkboard. To make amends Kenny writes him a kind poem. The second question asks, “Can you fix a broken promise?” And its answer remained for me the most impenetrable subject addressed by the storybook. The plot involves two toy soldiers: One of the soldiers feels that Kenny has broken his “promise to take care of them always.” The toy soldier has been chipped in four places and wants to run away. Overhearing this scheme, Kenny flies into a rage and places the soldier out on the windowsill in the snow. There is guilt and frustration, and a wish for love and friendship as Kenny watches the soldier in the cold and worries he has frozen stiff. When he brings the toy back to bed to warm him on his pillow, he tells the soldier that even when he smashes his toys together he still loves them. This resolution helps Kenny answer the question. “Yes," he responds, you can fix a broken promise, "if it only looks broken but really isn’t.” It is an answer that presents the kind of difficult truths Sendak’s work has become famous for.

The differences between lonely Kenny and asthmatic Kenneth can be difficult to disentangle. Despite the ways Sendak transposes the details of the sessions into literary form, leaving behind Kenneth’s family history, difficulties at school, and memories of being sent to live with his grandparents during the war, this material still lends force to the questions and answers that spur Kenny’s adventures. There are also clues that slip through. Sendak gives oxygen to Kenny’s worries over love and the seven questions pique our curiosity over earlier situations lived in shallow breaths where air was felt to be too thin.

Many of the clues are apparent in the ways language slides into new ideas across the two texts. In their first session, Kenneth whispers to his therapist: “Please, Dorothy, I don’t want to do anything.… Please don’t make me” and moves to look out the window of the playroom. Kenneth’s first steps towards the window communicate a sense of the work ahead. Kenneth will slowly move from his station at the window to communicating his needs to family members and, finally, developing friendships. The route out into a world of relations, paradoxically, will be a journey inwards for which the window frame serves as an ideal metaphor. From this scene we discover the answer to the question “what looks inside and what looks outside” that resounds in the storybook title. It is a metaphor that Sendak will return to in other books and that holds a special significance in for his beginnings as an illustrator entering the field of children’s literature.

"Out My Window"

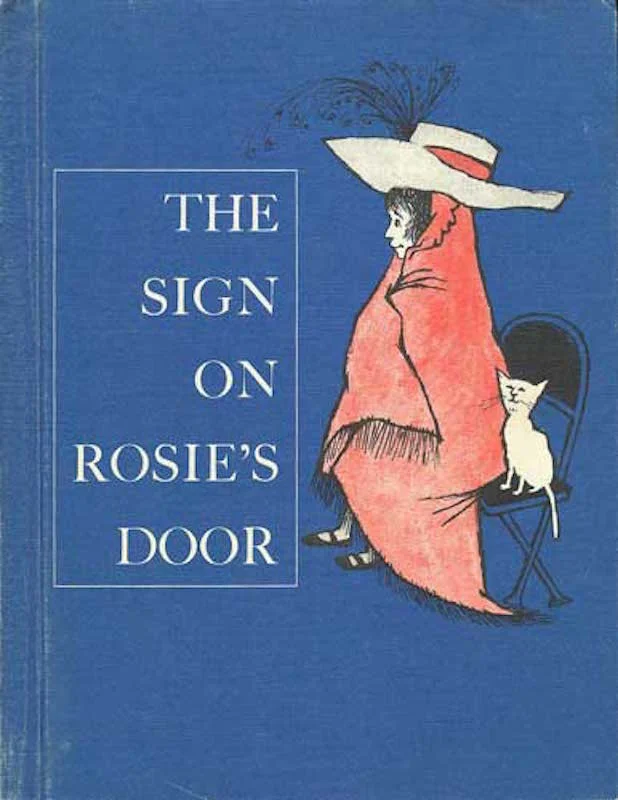

The pictures that lead to Sendak’s start as a children’s book illustrator come from drawings he made of children at play in the streets outside his parents’ Brooklyn home, what Sendak referred to as his "out my window" series. A little girl named Rosie lived across the street and often entertained neighbourhood children on her stoop. She was one of Sendak’s favourite subjects and later became the title character of his book exploring the creative resiliencies of children. Sendak took note of the effort Rosie put into holding the attention of the other neighbourhood children. Her creativity brought company, but she also wrestled with times when she was left without an audience. Rosie’s book would be published years later but Sendak once described her enduring inspiration:

There is Rosie, the living thread, the connecting link between me in my window and the outside over there. I did, finally, get outside over there. In 1956, after illustrating some dozen books by various writers, I did a Rosie and wrote my own. It’s called Kenny’s Window and in it I paid homage to Rosie’s street and house.

While the answer Kenny finds to the question of what looks inside and what looks outside may be unsurprising, it serves as only the beginning of an idea that stretches into Sendak’s entire body of work. The complicated idea set in a pane of glass is that for children too, looking deeply at both the personal conflicts of inner life and the disappointments and joys of being outside in a world of others can be most difficult. These conflicts mirror the confusion of pursuing a question which, once answered, may upset the ideals we hold for our most cherished relations.

Watching seven-year-old Kenneth gaze out the window, Baruch grants space to his plea: "This is a place where you can do what you want. You can do nothing if that’s what you want. You don’t have to live up to anything here. You don’t have to be a big boy. You can be a baby, even. […] You can play you’re my baby if you wish…"

And Kenneth climbs into her lap. In these first sessions Kenneth will find a way to explore what troubles him in the comforts of curling up in the analyst’s lap and other ways of pretending to be her Baby. He is big for his age and later, when the therapy is winding down, they laugh about how his “wants [can] get as big as an elephant’s:” “too big to be fed.” The therapy becomes a search for ways of wanting that can be accommodated by both his family and himself.

Gradually, Baruch and Kenneth begin to name his wishes, what holds them back, and some ways he might communicate his wants. Loneliness brings a terrible fear that love can be lost or his parents may send him away. These fears are sticky matters for Kenneth and they find expression in various indirect forms, including wheezing asthma. His wishes are hard to pin down; he tries to act them out with toy soldiers. It is a game where Kenneth leads the American attack against the Germans. Yet, the allies, for all Kenneth’s efforts, can’t seem to land their targets—and between tight breaths the German soldiers continue to escape unharmed. When Kenneth replaces the toy soldiers with figurines of a family, the targets become clearer: The frustration and fears that come from not being able to communicate an essential wish for love map onto a history that predates the battles played out in the analyst’s office.

Sendak captures the stakes of these conflicts in the question: “What is a very narrow escape?” Such a question involves Kenny in a game of risk where he leans off the bed and catches himself just in time. Baby the dog finds Kenny dangling inches above the floor and asks what he is doing. When the trick is explained Baby recognizes a narrow escape. Kenny describes how sometimes he, like the asthmatic Kenneth, holds his breath for as long as he can just to see what it feels like. This brings a warning from Baby for there is also the peril of a very narrow escape. Kenny asks if Baby has ever had one. And with a shudder Baby replies, “yes,” as the memory casts a shadow over her.

Baby tells a story about the day she pretended to be an elephant. That day Baby couldn’t sleep because she was too big to fit under the bed. Nor did she eat because elephants don’t like to eat hamburger and she couldn’t reach for her favourite bone with such a long snout. On that day, Baby worried: “Kenny has lots of love for a little dog, but does he have enough for an elephant?” Just in time for supper, a very hungry Baby stopped pretending to be an elephant. Both boy and dog agree that it was a very narrow escape before Baby drifts off to sleep on Kenny’s lap.

Like Kenny, Kenneth has a dog, too, although his goes by the name of Hamburger. The secrets tangibly felt in the therapist’s playroom but which remain things to be kept from the self sometimes find their way into expression by imagining how mad Hamburger must be when left outside at night, how he might growl and bark, and even bite. If Kenneth could only be “real-happy-to-be-mad-Hamburger” he could leave muddy footprints all over Mother’s bed. It is these sorts of secret thoughts that become the material of Sendak’s fiction and of Kenny’s dream.

In her book on the impossibility of children’s fiction, cultural theorist Jacqueline Rose offers a close reading of Peter Pan and its various iterations. With reference to Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, Rose notes that this classic children’s story can also be read as a dream, even if J.M. Barrie’s play does not invoke this device. With regard to Sendak’s fiction, what does it mean when the dream is invoked as aid to both finding and protecting the child and his wishes? We are in a situation where fantasies cut into the tense relations of the family, where bodies are already felt to be too big, and feelings are too much, and there is so little space to go. To “pull thoughts out by their tails,” as Kenneth accuses his therapist of doing, can sometimes feel like bringing that intertwining of fantasy and reality into a kind of clarity where the dream and its meanings illustrate demanding truths. When the rooster returns at the end of Sendak’s storybook and asks, “What is a very narrow escape?” Kenny whispers back: “when someone almost stops loving you." This is the kind of enigmatic admission that is difficult to speak aloud, the kind of statement that evokes more questions than answers.

The question we are left with after reading Kenny’s Window is how dreams organize children's experiences of the world. For all of Kenny’s explorations—from finding a new friend, to the realization that a wish is something not yet fully known and so opens new desires and directions—the peculiar thought this book leaves us with is that dreaming seems to be a chief organizing feature of children's experiences. But dreams also seem to unravel the meaning of these experiences. In this way, Kenny's Window becomes the kind of object that games are made of—a place where things might slip to and fro between fantasy and reality.

—Lucille Angus is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Education at York University in Toronto and an early childhood educator. Her PhD thesis examined children’s perspectives of their experiences through literature, interviews, and case studies.

"Kenny's Window" © February 2017