The Fichu Dream

By CAI GLOVER

In 2017, choreographer and dancer Cai Glover was inspired to turn one of Walter Benjamin's dreams into a dance, just as Benjamin himself dreamt of turning a poem into a scarf: "It was a matter of turning a poem into a fichu," Benjamin wrote to his friend Gretel Adorno from an internment camp in 1939.

In the summer of 1939, the Jewish-German cultural theorist Walter Benjamin was working on his massive Arcades Project in the Paris library when he got word that he had been officially expatriated by the Nazi regime.

By September, the now stateless writer—along with thousands of other “undesirables” living in Paris at the time—was told by Paris city officials that he was to present himself at the Stade Colombe, the city's open air football stadium. This was one of several mass arrests, purges which would culminate in the infamous Vel’ d’Hiv Roundup of July 1942.

Benjamin spent ten difficult days and nights in the stadium, whereupon he and the thousands of other detainees were packed into sealed rail carriages and transported to "voluntary work" camps in the south of France. Originally built for Republican refugees of the Spanish Civil War, during WWII these internment camps were filled with foreigners, and then, eventually with French Jews. The final destination for many of these people would be the Nazi extermination camps to the east.

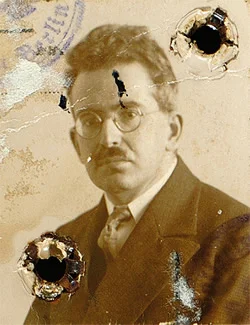

Benjamin's passport photograph from 1928. Courtesy of the Walter Benjamin Archiv, Berlin.

Benjamin was interned for several months at the Château de Vernuche, near Nevers. On October 12, 1939 while he was still interned in the camp and anxious about his fate, Benjamin wrote this astonishing letter to his friend, Gretel Adorno:

My very dear friend,

I had such a beautiful dream while lying on my cot last night that I am unable to resist my desire to tell you about it. There are so few beautiful, not to mention pleasant, things about which I can tell you. – This is one of those dreams, the likes of which I may have once every five years, that center around the motif of "reading." Teddie will remember the role played by this motif in my reflections on epistemology. The sentence that I spoke aloud at the end of the dream happened to be in French. This is another reason to give you an account of it in the same language. Doctor Dausse is with me in the dream. He is a friend who took care of me when I had malaria.

I was with Dausse and several others whom I do not remember. Dausse and I left the group at one point. After leaving the others, we found ourselves at an excavation. I noticed strange kinds of resting places almost at the bottom. They were the shape and length of sarcophagi and looked like they were made of stone. As I knelt, however, I realized that I was gently sinking into them like onto a bed. They were covered with moss and ivy. I saw that there were always two of these resting places side by side. Just as I was about to lie down on the one that was next to the one which seemed to be reserved for Dausse, I realized that it was already occupied by other people. So we kept on going. The place resembled a forest but there was something artificial in the way the tree trunks and the branches were arranged, which made this part of the scenery look like a shipyard. Walking along some beams and climbing up some wooden steps, we reached a kind of tiny, planked deck. The women with whom Dausse lived were there. There were three or four of them and looked very beautiful. The first thing that surprised me was that Dausse did not introduce me. This did not bother me any more than the discovery I made when I put my hat on top of a grand piano. It was an old straw hat, a panama that I had inherited from my father. (The hat is long gone.) When I took it off, I was shocked to see that a wide slit had been cut into the crown. There were some traces of red along the edge of the slit. – They brought me a chair. That did not prevent me from taking a different one that I placed a short distance away from the table where everyone was seated. I did not sit down. Meanwhile, one of the women was engaged in graphology. I saw that she was holding something I had written which Dausse had given her. I was slightly worried by her analysis, fearing that some of my personal characteristics would be revealed. I moved closer. I saw a piece of cloth covered with images. The only graphological element I could distinguish was the top part of the letter d. The elongation revealed an extreme aspiration to achieve spirituality. Appended to this part of the letter was a small sail with a blue border, and the sail was billowing as if filled by the wind. That is the only thing I was able to "read" – otherwise, there were only indistinct shapes of waves and clouds. The conversation turned on this handwriting for a time. I do not remember the opinions expressed. But I do know very well, that at some point I spoke these exact words: "Il s’agissait de changer en fichu une poésie" [It was a matter of turning a poem into a scarf]. I had barely uttered these words when something intriguing happened. I noticed that one of the women who was very beautiful was lying on a bed. When she heard my explanation, she made a movement as quick as a flash. She pushed aside a bit of the blanket that was covering her. It took her less than a second to do this. It was not to show me her body, but to see the pattern of her sheet. The sheet must have had imagery similar to the kind I had probably "written" many years ago to give to Dausse. I was quite aware that the women had made this gesture. But I was aware of it because of a sort of second sight. My bodily eyes were somewhere else. And I was not able to distinguish what was on the sheet that had been so surreptitiously revealed to me.

After this dream, I could not fall sleep for hours. Out of happiness. And I write to you in order to share these hours with you.

No news. No decision regarding our matter so far. The arrival of a "selection committee" was announced but we do not know when they will come. My health is not all that good. The rainy weather is not suited to improving it. As for money, I have none. We are not permitted to carry more than twenty francs. Your letters would be a great comfort to me. I am glad that Mme. Favez received Pollock’s instructions. A French friend is taking care of my belongings in Paris with the help of my sister.

Apart from your letters, what would offer me the greatest pleasure would be for you to send me the proofs (or the manuscript) of my "Baudelaire."

Please forgive any mistakes you may find in this letter. It was written amid the constant din that has surrounded me for more than a month.

Need I add that I am eager to make myself more useful to my friends and to the enemies of Hitler than can be in my present state. I never stop hoping for a change and I am sure your efforts will be joined with mine. Remember me to all our friends

Love, Detlef

The first page of Benjamin's letter to Gretel Adorno, October 12, 1939. Courtesy of the Walter Benjamin Archiv, Academy Akademie der Künste, Berlin.

Benjamin was released from the camp in January as a the result of the concerted efforts of his friend Adrienne Monnier and the French PEN Club. He returned to his apartment at 10 rue Dombasle in Paris to continue work on his Arcades Project, but by the spring of 1940, the Nazis were threatening to seize the city.

Benjamin deposited his manuscripts and some of his books with George Bataille at the Bibliotèque Nationale, and on 13 June 1940, one day before the Germans arrived, he and his sister joined the millions of Parisians who fled the city.

They landed in Lourdes, in the south of France, and Benjamin made plans to emigrate to the United States via Portugal. In September, he joined a small group of refugees who hiked across the French–Spanish border, arriving at the coastal town of Portbou, in Catalonia. On the day of their arrival, the Franco government cancelled all transit visas and ordered the Spanish police to return all refugees to France.

Expecting to be turned over to the Nazis, Benjamin took his own life on 25 September 1940. A few weeks later, the embargo on visas was lifted again. As Hannah Arendt described: "One day earlier, Benjamin would have gotten through without any trouble; one day later the people in Marseilles would have known that for the time being it was impossible to pass through Spain. Only on that particular day was the catastrophe possible."

Photograph by Heinrich Hoffmann (seized by the US government after WWII): Adolf Hitler visits Paris with architect Albert Speer (left) and artist Arno Breker (right), June 23, 1940. Courtesy of the US National Archives.

Cai Glover is a dancer and choreographer, currently with Cas Public, a dance company based in Montreal. Glover has danced with companies in Vancouver, Atlanta, and Kelowna and has worked with a wide variety of choreographers, including: Henry Daniel, Paras Tarezakis, Josh Beamish, Judith Garay, Vanessa Goodman, Simone Orlando, Lauri Stallings and Gioconda Barbuto.

"A Fichu Turning" (2017), Art Direction, choreography, music, and performance by Cai Glover; Director of Photography and editor: Kenneth Michiels; Lighting: Emilie Beaulieu; Thanks to Kopergietery for the time and space.

Quotations (in order): Jacques Derrida, “Fichus: Frankfurt Address” (2002) in Paper Machine; Walter Benjamin, “Letter to Gretel Adorno, October 12, 1939” in The Correspondence of Walter Benjamin; Jacques Derrida, , “Fichus: Frankfurt Address”; Hannah Arendt, "Introduction: Walter Benjamin 19892-1940," in Illuminations. Additional text provided by Sharon Sliwinski.