Farming Images:

The Documentary Practice of Soumya Sankar Bose

Santasil Mallik

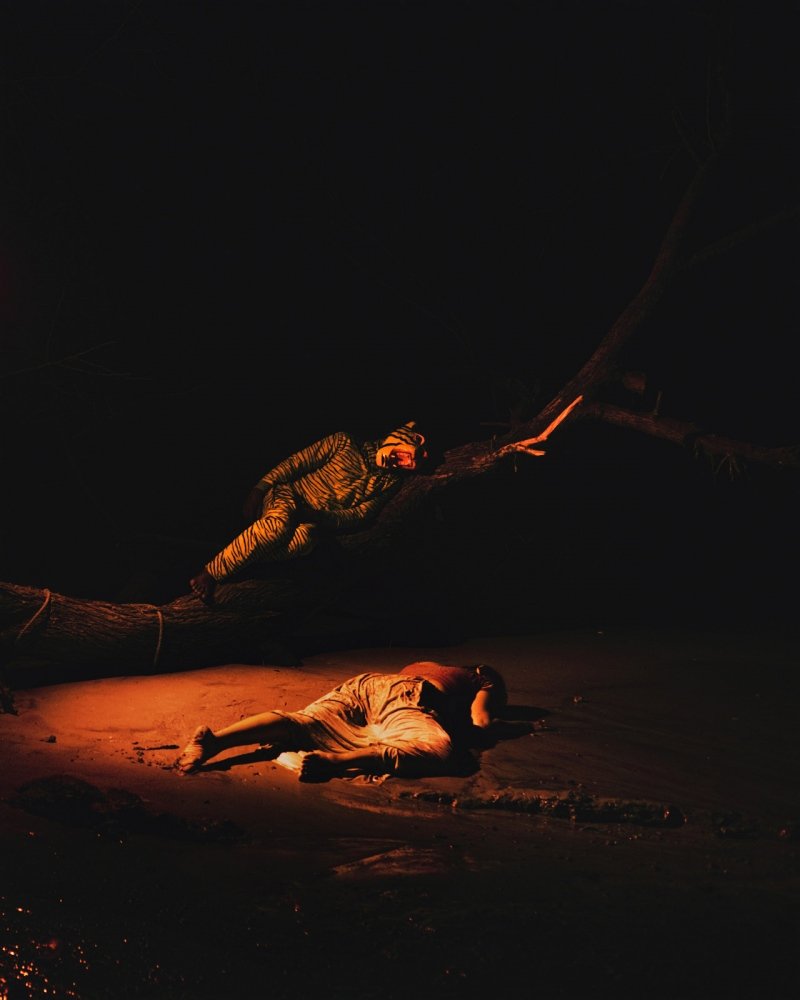

She dreams that she sits on a chair beside a window in the room in which her sister died. In the dream she returns home from an unknown war while a dead body lies in the bed. The identity of the dead character is never clear to her. Moreover, the dead person is adorned in the attire of a warrior... Did the corpse belong to her sister? Was she fighting for acceptance? Or, was it the culmination of her mother’s firm belief that she could not fall in love with another woman?

– From Full Moon on a Dark Night

Such inchoate images compose the richly textured work of the Indian documentary photographer Soumya Sankar Bose. In his project, Full Moon on a Dark Night, this dream vision of his friend, Vaishali, served as a creative impetus to explore the appearances, facades, and performances of queer identities. Awarded the Magnum Foundation’s Social Justice Fellowship, Bose’s project engages with the dreams and imaginative projections of his close ones as they navigate India’s decriminalisation of homosexuality in 2015 amid unchanging prejudices.

Bose’s method involves a collaborative exercise of translating these accounts into staged tableaus, resulting in meticulously constructed theatrical scenes that blur the boundaries between reality and fiction. Indeed, in Bose’s emerging photographic oeuvre, the visual field unfolds as a continuum that includes familiar ways of documenting reality as well as new methods for documenting the inner worlds of his collaborators.

In my conversation with the artist, we reflected on the nature of his image-making practice and its implications in understanding the contemporary horizons of documentary photography.

Santasil: How did you realise that exploring dreams would be a relevant point of departure for this project?

Bose: When talking about ‘documentation’ in documentary photography, we try to document what we can see. But we also see when we sleep, and that became a part of my documentation. Maggie Steber once asked me why I describe my work as documentation when it is mostly fictional. But then, I document our memories and psyche, which is also a kind of documentation. It is very personal because you see a dream and describe it to me, and I must find a way to document it. My practice concerns the inner lives we carry in our heads for years of living with complicated scenarios. This project started similarly when my friends began sharing their dreams and nightmares with me. Interestingly, I also have certain kinds of dreams, which often get mixed with theirs. It is precisely where my work grows like a collaborative project; we develop it together.

Santasil: How do you translate dreams into images? What does the process usually look like?

Bose: Firstly, I conduct interviews and pen down notes in detail. Every person narrates multiple variations of their dreams and desires, among which we focus on the ones with which we feel more connected. Following the interviews and transcription, I do rough sketches of selected scenes and show them to the narrator, deciding the ones to stage and shoot. Afterwards, we scout for locations, the perfect time, props, and other necessary elements. One friend, for instance, used to have a recurring dream of him conversing with a teddy bear. So, we started looking for a teddy of the right size, form, and colour, bearing at least some similarities with the one in the dream.

The activity of staging constitutes an essential role in Bose’s practice, stemming back to his debut project, Let’s Sing an Old Song, where staged performances feature meta-thematically. The project concerns the unemployed but once-celebrated Jatra artists enacting their most memorable characters in front of the camera. Jatra is a dying folk theatre form dating back to the 16th century Bengal, employing a clamorous mixture of songs, monologues, and instrumental music to communicate popular stories from mythologies, historical episodes, or contemporary social issues. Several factors led to the decline of the Jatra, including the successive partitions of Bengal (1905 and 1947) and increasing communal tensions. Performances involving Hindu folklore were discontinued in Muslim-majority East Pakistan (later Bangladesh in 1971), while those featuring eminent Muslim characters stopped playing in Hindu-majority West Bengal.

Let’s Sing an Old Song is inspired by Bose’s uncle, who was once involved in Jatra but later joined a railway factory to sustain himself. Collaborating with the renowned stars of a yesteryear form, he attends to lingering images and characters resting within them. As Bose notes, “these people in their 80s and 90s were describing the characters they used to play 30-40 years back from a perspective where their lives and careers have drastically changed.” He likens the re-enactment of the characters to the recalling of dreams, where we imaginatively try reviving memories and details not available to consciousness.

Bose: In the post-magical realism era, you never know what is real and what is dreamt. Maybe, what you are seeing now is a live transcription of a dream and what you see while sleeping are fragments of real experiences. Of 80 years of memory, when they are trying to describe a character from the past, they are basically connecting with their subconscious mind, thereby seeking and mixing up a lot of things from their memory bank. That is why I never asked them to play the characters on stage, but in their situated reality. I asked them about their favourite places in neighbourhoods, places they see in their dreams, their favourite characters etc. Later, we merged them and took pictures. It is like creating a dream, maybe not the image they have seen, but a new composite one. The image I make does not exactly exist in real life, but their individual elements do. This is also how our memories work, constantly fusing things.

Santasil: Do you conceive dreams and reality as separate realms or do you envision them in continuity?

Bose: It is interesting because we never think about it! Both in dreams and reality, we are witnessing. We are seeing from a perspective, seeing everything except us. Similarly, the Jatra is happening around us where people are playing characters, be that of a professor, student, or a tea seller. But this tea-seller is also changing, becoming someone’s father after some time. We all are witnessing, and our life is nothing but memory. There is a line from my upcoming film, which says, “you have to begin to lose your memory, if only in bits and pieces, to realise that memory is what makes our lives. Life without memory is no life at all.”

The relationship between memory and the constitution of personal identity has been a cornerstone of the empiricist philosophical tradition dating back to John Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding. The idea of the self is built through a process of organizing one’s memories in narratological continuity. This sense of the importance of memory was revived in the field of trauma studies during the 1990s, which turned to Freudian theory to underline the unassimilable nature of traumatic events and ensuing psychic crises. In this discourse pioneered by Cathy Caruth, Soshana Felman, and others, trauma remains outside the scope of conscious memory and narrative representation. Later theoretical developments critiqued such essentialised understanding of what Caruth calls “unclaimed experience.” These critiques started exploring the generative possibilities of creatively reconstituting traumatic memories. Foregrounding a reparative approach, they explore the dynamic relationship between experience, language, and identity.

Soumya Sankar Bose’s documentary projects feature an aestheticized approach towards traumatic memories, which aligns with the critiques of traditional trauma studies. While many of his projects indirectly index or play out in the context of underlying historical and political crises, in Where the Birds Never Sing, Bose directly addresses an episode of extreme violence perpetrated by the West Bengal state government in India. The project concerns the Marichjhapi massacre of 1979, where the incumbent Left Front CPI-M (Communist Party of India - Marxist) government torched settlements and murdered thousands of refugees from the 1971 Liberation War of Bangladesh who resettled on the Marichjhapi island in the delta region of West Bengal. Police closely guarded the episode and the Left government has steadily denied any involvement. With scarce archival resources and a few survivors remaining, Bose created a compelling account of the incident that to this day remains shrouded in historical denial. By blending landscape images, portraits, archival traces, as well as theatrically constructing scenes derived from oral testimonies, nightmares, and popular myths surrounding the massacre, Bose has developed an inventive and gripping way to explore and represent traumatic experience.

Santasil: In the previous projects, you talk about witnessing across dreams and reality. But what kind of witnessing is a traumatic witnessing? How did you attend to the witnessing of the survivors, which is very difficult to talk about in the beginning?

Bose: I proceeded differently in this project. First, I started meeting the few academics and people who have researched on the massacre for a long period of time like Ross Mallick (who lives in Canada now), Annu Jalais, and other regional scientists like Tushar Bhattacharjee and Madhumoy Pal. These people lived during the time of the massacre, listening about it from contemporaries. Later they met the survivors and started writing about them. It is interesting because they met the survivors in the 1980s and 90s, whereas I met some of the same people after 30-40 years. Therefore, many things are forgotten, added, imagined, lessened in effect, or even adopted from things they have read somewhere later.

Memories are the key point here, but our emotions also matter. During the 80s and 90s, it was different. The CPI-M government was still ruling and the anger against them was more powerful than in 2017 or 2018 when I was working on the project. My work was mostly about what one still carries from an episode 40 years back. You have 40 years of memories to overlap the incident and yet not completely obliterate it. When I started working on Jatra, it was about striking memories they did not want to lose, but in Marichjhapi it is the same generation carrying traumatic memories they would rather lose.

Santasil: Did it affect the way you approached staging the images?

Bose: Exactly. In the Jatra project, the artists are playing their characters and are happily re-enacting their memorable roles. But in the Marichjhapi book, there are many staged images where I have used professional actors instead of the survivors. There are a couple of pictures where the survivors have wilfully consented to be in them, posing as protagonists. But there are many pictures where much younger actors are playing the characters. I cannot ask the survivors to play those characters, which would be like a torture. That is why my approach here is way different from the previous ones. There are only ten photographs of survivors, while rest of them are landscapes and other constructed scenes that I have imagined after engaging with them over time.

Santasil: In your previous projects you had a dialogic process of listening, writing, interpreting, and shooting images with your collaborators, but how did you interact with the survivors here?

Bose: In the physical book, or even in exhibitions, the last image of a woman with bird mask, for instance, is always presented alongside a letter. A letter written by one rape survivor. The book also starts with a conversation where I am looking for that lady. But when I eventually met her, I did not feel like taking a picture. Rather I took the letter, translated it in English and placed it alongside the bird-mask image. I thought of constructing something which will guide the viewer in thinking about the incident instead of thinking about the actual person who have faced it. Here, you are not violating the survivor’s personal space, but creating a different space where you work through the same emotions. You feel the same connection without knowing the person. The book ends with the letter put inside folded images of a character in bird mask, circling back to the conversation in the beginning.

Santasil: How did listening to these disturbing testimonies affect you? Did you also started dreaming of certain images? Did they play a part?

Bose: Yes, I think in all my projects my dreams play a part. I do not just narrate the stories of others, but also mine. My photographs are not made for assignments, where you hunt for images. I farm my images in my own lab. We farm different things: rice or vegetables during different seasons, but we farm in our land - the base. This base is comprised of our dreams. Then we are collaborating with other people, borrowing seeds, and producing something grown out of a partnership. Starting from the Jatra project to the one on which I am currently working, I always connect them with my journey. None of my projects come suddenly to me from an urgent journalistic concern. They are often regional, less talked about, or involve a vast temporal space.

The metaphor of farming images could not have been more apt to describe how Bose interacts with dreams. Here the mind features like a greenhouse where visual elements grow through collaborative labour. Intersubjective nurturing and cultivation of traumatic experiences becomes a way to work with narrative absences in history and memory.

While Where the Birds Never Sing addresses the collective memory of a massacre, Bose’s ongoing project, A Discreet exit through Darkness, relates to a traumatic subject within his family. The project digs deep into the curious disappearance of his mother during her childhood in the autumn of 1969. She reappeared three years later but did not remember anything due, in part, to a cognitive condition called prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness. Bose writes, “it is almost as if her memory of that period has been somehow wiped clean.” Therefore, his mother lives her childhood through two phases: before the disappearance and after her rescue. A Discreet exit through Darkness navigates this narrative void by rummaging through intra-family conflicts, the alleged involvement of child traffickers, superstitions of ghosts and evil eyes, personal fables, and political turmoil pervading that period.

Santasil: In this project you are using personal accounts from your family, concrete historical information from archives, and various other sources to weave a language that can possibly address those three years of your mother’s disappearance. Would you like to speak about the project a bit?

Bose: My mother was missing for three years, from 1969-1971. My grandfather was looking for her and during the searching process he died in 1971. My mother was rescued a year later after his death; therefore, they never saw each other. It is a very disturbing period for my family. For me, it is interesting because both, my mother and grandfather, have different perspectives of those years. The first chapter of my work to be shown at Experimenta Mumbai until April [2023] is from my grandfather’s perspective… what he thought about the disappearance, what he went through, and what I imagine him to be going through.

The second chapter is from my mother’s perspective, who is alive and helping me with lots of incidents. I am trying to put them together and making a world. Both the perspectives are fictional. For making the films and images in this project, I am putting together newspaper reports, state archives, and other accounts from that period. When you will read the book or see the films and images, you will get an idea about contemporary historical events. They are not how I have described them because newspapers always provide news minus characters. I am using concrete news information and adding flesh and blood to them to turn them into stories. Like in my other works, you always wonder whether a particular thing is real or not.

Santasil: I was wondering, do dreams always have concrete references? Can they emerge from sites not experienced?

Bose: It depends! I am not a trained psychologist, so I might not be the right person to talk about it. But from my ongoing artistic practice, I can reflect upon it. Currently, I am writing a character in the film from my project’s second chapter. The character is blind but she does not know that she is. It is because she has lost certain amounts of memory from her mind, including the incident which made her blind. It is not a real character, but I read about a similar character in a psychiatrist’s case study who diagnosed a similar patient. The patient lost most of her memories except for ten to fifteen years of them, but gradually she also became schizophrenic. Therefore, she was constantly imagining characters in front of her even though she did not have vision. She used to imagine and talk with characters derived from those fifteen years of memory. I came across a very small reference of this case in a book and converted it into a character in my book, adding dialogues, settings, and scenes. This is just a reference emerging from my artistic practice in response to your question.

Santasil: What book was it where you came across this case?

Bose: Ah, some post-Freudian psychologist in the late 70s and 80s. I do not remember it now. I always have a problem in remembering things because of prosopagnosia inherited from my mother. My brain cannot remember faces and names, I am very bad with them. But my brain can easily remember incidents, time, and date. Sometimes, I forget my best friend’s name, therefore, I always save contact numbers by other details. For example, to save my school friend’s contact, I write the name, followed by the city where I met him, the date and time period during which he was my friend, like 2005-2007. Later, when I want to call somebody whose name I cannot remember, I type the time period on the phone and search. I also keep forgetting the name of my studio assistant, whom I meet every day.

Santasil: You do not forget visual memories?

Bose: No, only alphabets and faces.

Santasil: Not landscapes?

Bose: Not really, my brain works better than Google Maps. I can visit a place after several years and recognize them easily. I also remember voices. Everyone has a certain way of talking, from which I can easily recognize them. Even if someone tries to dupe me by calling from a different phone number and faking a voice, I can easily recognize the caller if I have heard that person before.

In Soumya Sankar Bose’s artistic practice, the complexities of representation remain a persistent concern across varied historical and political issues, expanding the critical parameters of documentary photography beyond evidentiary truth and accuracy. He engages in the practice of documentation while constantly undoing the generic assumptions of such an exercise. Bose seems to be a part of an emerging global sub-culture in documentary photograph, where practitioners are increasingly experimenting with hybrid forms of representations as they work with different media and genres. Fictional and subjective interventions in articulating complex narrative layers around a topic have become an intrinsic component of this orientation.

However, as Bose reminds us: “it is not the time to claim such tendencies as a contemporary trend. Perhaps it is too early to do so.” For him, the phenomenon of dreams and their narration manifests as a methodological element in exploring the languages of representation, allowing him to manoeuvre profuse sources – known and unknown. One noteworthy term that emerged from our conversations, articulating the shift from seeking established truths to expanding the very conceptual rubric of truth is what Bose calls “farming” images. Contrary to the more familiar phrasing of “hunting” images, Bose exclusively interacts with his collaborators over dream landscapes, nurturing images equally thoughtful and hauntingly evocative.

Soumya Sankar Bose (b. 1990, Midnapore, India) is an artist based in Kolkata, India. He reconstructs archival materials and oral history into photography, films, alternative archives, and artist books. Bose’s hybrid mode of practice interweaving long-term research and engagement with local communities including his own family history accentuates certain subaltern experiences of the marginalised yet resilient in post-Partition Bengal. Enmeshing fiction and reality, Bose’s work opens up daring realms of memory, desire, vulnerability and identity. Most of his projects unfold in several chapters and various forms after yearlong conversations and engagement with a marginalized community. Bose has been awarded many prizes and grants from various organizations, including Magnum, Aperture, the Henry Luce Foundation, the Foundation for Indian Contemporary Art, and India Foundation for the Arts. His books and prints are in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Ishara Art Foundation, among others. Soumya Sankar Bose is represented by Experimenter Gallery, Kolkata and Mumbai, India.

Santasil Mallik is a writer and visual artist pursuing his PhD in Media Studies at the University of Western Ontario in Canada. His research interests concern the political aesthetics of documentary media in conversation with narratives of political violence in India and South Asia. As a practitioner, he works around experimental cinema and video art.