I am nothing…in this vulnerable exposure of myself to a letter from you, on the absolutely other side.

...

Between her and me, it is as if it were a question of life and death. Death would be on my side and life on hers.

—Jacques Derrida, H.C. For Life, That is to Say…

Him—expecting the to-come. Me—waiting for the Comebacks, the Revenirs—and thus expecting Revenants.

—Helene Cixous, Insister of Jacques Derrida

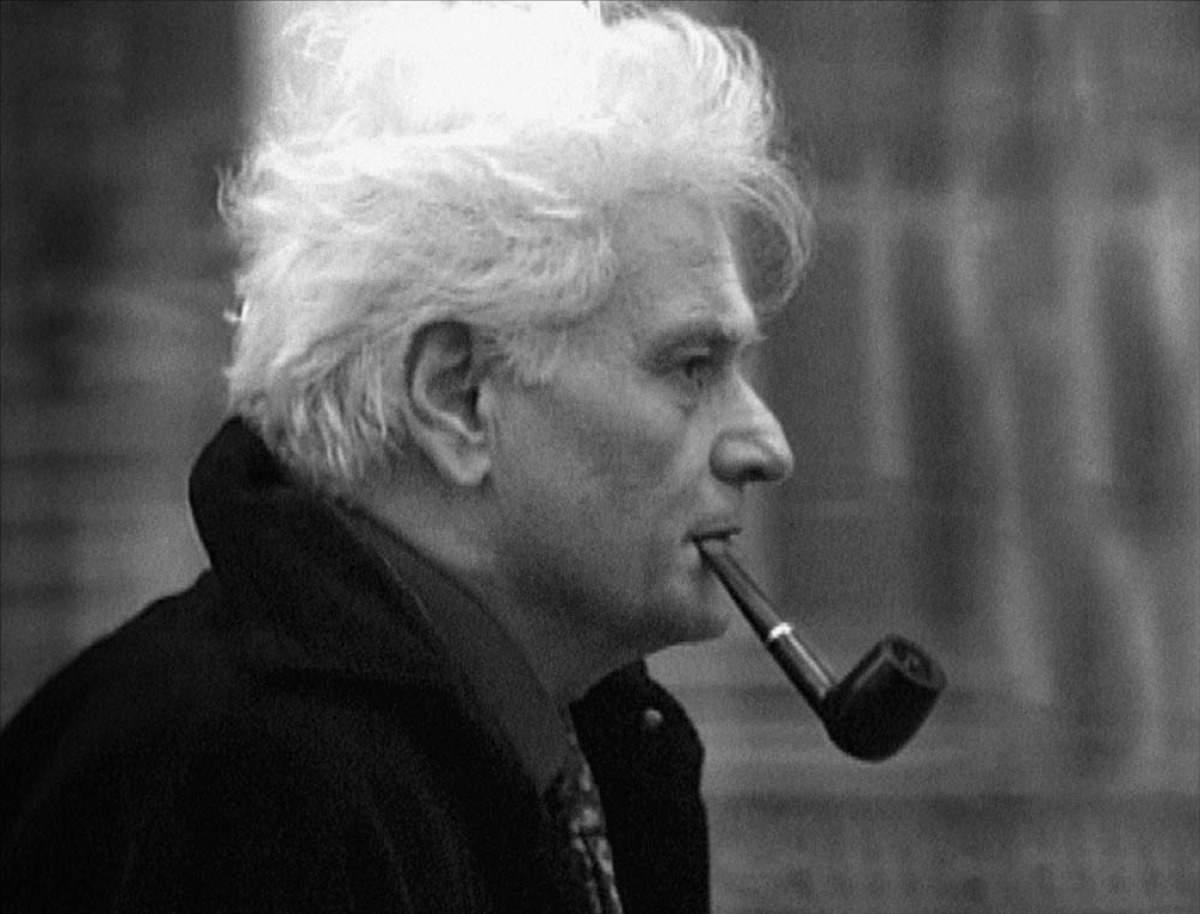

The above quotations give the tenor of a life-long debate between the French philosopher and founder of “deconstruction,” Jacques Derrida, and the French writer and philosopher, Helene Cixous, someone Derrida once described as “the greatest writer in…the French language…a poet-thinker.” Cixous, for her part, described Derrida as one of the “incorruptibles” of philosophical thought. Their debates often turned on the subject of death and on the role of death in the life of the mind. Cixous remained firmly on the side of life, or at least, on the side of “Comebacks.” Derrida, meanwhile, often found himself drawn to the other side, to Death, the side “expecting the to-come.” Both of these thinkers spoke, read, and lived as if their dialogue were a matter of life and death. The texts they devote to each other are like odes and elegies to their friendship—tributes to what it means to give and take sides between life and death.

There is a certain indissociability, though, in the expression of their positions; something ties his expression inextricably to her and hers to him. Derrida is nothing without a letter from Cixous’s side, he writes. Cixous, from her side, exposes him in her letters. They are on each other’s side, we might say, the poet-thinker and the incorruptible philosopher, but they are not on the same side.

Film still from Derrida (2002), a documntary by Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering Kofman.

One of the places Cixous and Derrida did come together was on the subject of the dream. In her tribute to Derrida, Cixous recounts how the desire of the dream always preoccupied them both, visiting them each, always “unforeseeable” and “unforedreamed.” She recounts as well how all their lives they talked about dreams, about dreaming and writing. She calls Derrida “the intermittent dreamer” and herself “impenitence itself.” They were both occupied in advance by the dream they couldn’t dream, and by the desire for the dream always still undreamt, always still to come, unrepentant on one side, and sometimes still dreaming on the other. Cixous and Derrida write often of their dreams. The dream stirs this relationship between the unforeseeable in life, on the one side, and those lives, on the other side, that are lived in conversation, lived as talk between intermittent dreamers, dreaming of life and of death, in life, dreaming so as to keep dreamers alive.

In his 2001 Frankfurt Address, "Fichus," published in Paper Machine, Derrida-the-philosopher, from his side, noted the negativity that philosophy sets against the dream, which he refers to as “a wound.” For Derrida, philosophy for the philosopher is like being awake, precisely, like awakening in the contemplation of death. And yet he can’t help but speculate over another kind of response to the dream, another side, a “no less responsible” response, not from philosophers, but from poets, writers, or essayists, from musicians, painters, playwrights, or scriptwriters. This other responsible response comes from the poets’ side, Derrida imagines, from the writers, from Cixous perhaps. As opposed to the philosopher’s negativity, the poets’ response would affirm the dream, and affirm the dreamer’s thought therein and her capacity to utter what Derrida calls “the truth of the dream: the meaning of the dream that does not succumb to the night of nothingness, that lives, rather, a meaning dreamed-of living, writing, perhaps, as opposed to dead and awaiting awakening." This response on the other side of awakening comes, writing, from Cixous’s side, from the side of life that is already on the inside of the dream.

The philosopher wakes from the dream and is on the side of Death. Death is this incorruptible awakening from dream life: an endless sleep without dreams. Against the side of the philosopher, Derrida imagines Cixous’ side: a place of “vigilance” for the lessons and lucidity of the dream, somewhere from which to open a different kind of thinking of the relation between the possible and the impossible. There is development of thinking in dreaming, he says, a quite different thinking, though, a procedure of thought that is developed out from the dream, unfolded therein, impressed. Derrida speculates from Cixous’ side, vigilant, welcoming of what dream thinking means for the life that receives it—up to the end.

The opening page of Hélène Cixous's The Insister of Jacques Derrida, trans. Peggy Kamuf (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2006)

Coming to Writing as We Dream

Soon after Derrida’s death in the fall of 2004, Cixous writes her book, Insister of Jacques Derrida. In the text she returns again to the subject of their irremediable difference: the sides of life and death. This time, however, the debate is haunted by the tragic outstripping of the body by the text—Derrida is incurably on the absolutely other side. In response to his death, Cixous writes—indeed, she insists. She and Derrida, both, have made much in writing of the relationship between the act of writing and the fact of death, of how writing ignores living limits, reaching beyond existence—writing becoming Being. And so Cixous writes after Derrida’s death and in this way thinks again with Derrida on the subject of death. She writes and insists and thinks so as once again to refine their respective positions on either side of an aporia: the paradox of death in life, the inconceivable death of the other in the life of the self.

Insister opens with a dream. The dream “comes to sign this text.” The dream, too, like the text, comes after Derrida’s death, coming in order to sign the text with the authority of his name, he for whom the dream comes after. Cixous calls the dream a vision—a vision in which she and Derrida are two mice are playing football. She is in goal and Derrida is preparing to shoot. They are separated by sexual difference: a “little girl mouse” and a “hefty male,” she says. Writing the dream down, after dreaming it, Cixous directs Derrida’s attention: “Notice,” she writes, “the dreaming woman is on your side.” Derrida will score for sure and yet all at once he bursts out laughing in the dream: “the spectacle of the adversary who is really frightened makes [him] laugh but benevolently.” The dream is a vision of sides, of their misgivings, and of the benevolent laughter of the adversary.

The subject and figures of the dream give pause. Why mice? What do mice signify for Cixous? And what does the playing of football mean for these two intellectuals? And, finally, why laughter? What does a dream mean by laughing?

There are mice in Cixous’ writings and not just in her dreams. In an essay entitled “Coming to Writing” Cixous distinguishes between a mouse and a prophet in a description of the attempt to write. “A mouse is not a prophet,” she asserts and then casts herself in the role of the mouse. The mouse does not have “the cheek” to claim her book from God, as the prophet does. The prophet, then, is the man whose text is the received word of God. The woman, on her side, is a mouse, her book comes from elsewhere, from another side. Writing was in the air around her, the mouse, says Cixous, it comes abruptly and is always “close,” “intoxicating,” “invisible,” and “inaccessible.” The mouse, then, is a position in relation to language. Sissel Lie has described how this powerful text, written by the fearful little mouse carves a position in language not in spite of her status as mouse, but because of it. If Cixous writes, it is because she is a mouse, and if she is a mouse, Cixous clarifies, she belongs to the “flying-stealing-mice.”

The mice of Cixous’ dream might also refer to a position in language, to a particular place from which writing comes, intoxicating, to the woman. The position of the mouse is decidedly a feminine one for Cixous. And while Derrida in the dream is represented as a “hefty male” mouse, he is still not a prophet. The dream, figuring Derrida as a mouse, gives him the woman’s position in language, gives him the side of the dreaming woman, the side of the mouse which Cixous herself is. In other words, Cixous’ dream-wish is for her friend to write from her side. “The dreamer invents his own grammar,” Derrida once proclaimed. The dreaming living woman invents her own grammar. In this way the dream is a dream of mourning. Or rather, it is a dream that defends against mourning. Derrida is dreamed into the position of the mouse who is going to score and we can note that to score in French also means to mark (“marquer un but”): Derrida-the-mouse is braced to leave his mark, his trace—writing, living, from Cixous’ side.

We can ask a further question of the dream: why are the mice playing football, specifically? There is a thread here as well. In a recent biography simply titled, Derrida, Benoit Peeters tells a story of exclusion that traces the contours of Derrida’s life and philosophy. The narrative depicts an outsider with no choice of sides, and who finds consolation in pulling sides apart, in unbinding the signifiers on either side. Peeters relates Derrida’s expulsion from high school in 1942 for being Jewish in French governed Algeria. Derrida has recounted elsewhere that his expulsion marked his becoming “the outside.” He describes how Derrida then found in football a “taste for a freer life,” dreaming even, then, of becoming a professional footballer. Peeters also mentions that Derrida shared the story of his expulsion with his dear friend Cixous.

Football was for Derrida the freer life, and we can assume Cixous knows this. Football is the outside Derrida became in being expelled. In her dream Cixous joins Derrida on the pitch, together they indulge his passion for (a freer) life. Cixous dreams from his side, granting his desire to be a footballer, to live freely, a desire she can only grant him dreaming. Her letters, putting into words the vision of the dream, expose the vulnerability of Derrida’s desire. Her dream, giving Derrida the other side, the freer life outside, exposes her to the vulnerability of her own desire. This is what the dream is, after all, in general: the freer life outside on the inside that exposes therein the vulnerability of our desire.

Finally, then, there is the question of laughter in the dream, the dream that laughs from the other’s side, the side as well, for a time, of the dreaming woman. Here again we can turn to one of Cixous’ texts for a cue. Cixous has treated the laugh before, adding depth to the laughing figure and significance to the political valence of the act and experience of laughter. Her essay “The Laugh of the Medusa” opens with her proclamation that she will be speaking about women’s writing, about what it will do. For Cixous, to write is to write the self. She seeks to bring women to writing, “from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies—for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal” (39). We might be given to wonder, then, if the goal Derrida is poised to score in the dream is this same fatal goal, this same reason and law. For Cixous it is a question, in any event, of coming back to writing. In writing about laughter Cixous writes about what writing can do, and about what women’s writing will do. As Lie argues, Cixous proposes laughter as a libidinal strategy for writing, an inner strength and cheerful force that outwits Power. Lie asks what happens to the warrior when Medusa does not threaten him, but is laughing?

The dream exchanges Derrida’s power to score for the benevolent force of laughter. For Cixous laughter is the writing strategy of women, an intensive dimension of what women’s writing will do. In making her beloved friend laugh in the dream, Cixous again gives Derrida another side: instead of scoring the warrior’s fatal goal Derrida laughs the Medusa’s laugh. He is granted the laughter that belongs to the dreaming, writing woman on the absolutely other side.

The symbolism tendered by Cixous’ dream of Derrida uncovers, among other things, an effort to refuse his death, to offer him, in three figures—the mouse, the footballer, and the laugh—that side which belongs to the dreaming woman, the side of life. The dream simultaneously mourns and defends against mourning. It is the vision of a conflict over mourning: bringing to life Cixous’ despair over the loss of her friend while reveling in the contradictions of her desire to bring him back to life. Dreams catch us, so to speak, in the act of covering our tracks. Cixous has called the dream “the place where we never lie.” Her desire to share her side with her friend is complicated by her desire to grant him his own desires and also to accept the side he is on, to accept his death. In this way Cixous’ dream brings to the surface her ambivalence in mourning: loving her friend, hating his death. Cixous has written about how we should try and write as we dream, and write as our dreams teach us, without shame and in an effort to face that which is inside us, self and other both. Cixous repeats, in this way, Freud’s original question about dream life: what does making something of the dream make of the dreamer?

Dreaming, We Think

Cixous’ dream is an early effort to symbolize her feelings over the loss of her friend and to represent the wish behind her thinking over her side and his, life and death. Dreams picture desire in a particular way, though, and the question becomes: what does the dream signify for the going-on thinking, living, writing, and dreaming of she who has lost someone and then dreamed? As Freud remarked in On Dreams:

What stands in the foreground of our interest is the question of the significance of dreams, a question which bears a double sense. It inquires, in the first place, as to the psychical significance of dreaming, as to the relation of dreams to other mental processes, and as to any biological function that they may have; in the second place, it seeks to discover…whether the content of individual dreams has a “meaning,” such as we are accustomed to find in other psychical structures.

This is another way to ask one of the questions Derrida puts to the philosopher: What is the difference between dreaming and thinking you’re dreaming? In other words, how is the unfolding of meaning in dream-life related to those other mental processes by which the dreamer comes to understand her own psychical development and emotional growth? It is a question of how the development of dream-life in particular is related to the human condition of development in general.

If dream material, as Freud contended, contains all the characteristics of waking thought, then how might dream-ideas and dream-thoughts also be related to the developmental vicissitudes of the dreamer? To this question can be added the corresponding idea that getting in touch with and reflecting upon the significance of dreams is also how the human develops, by giving meaning to the changing conditions of the life of the mind. Human development in this sense also refers to a process of attributing meaning to the living conditions of change, both personal and interpersonal—a dynamic especially palpable in dreams. After all, development is a situation of emotional growth that we are never on the outside of and in this way it is lived always alongside others and must to a certain extend also be dreamed—up to the end.

Leaving Ourselves to One Side

Dreams facilitate coming and going; dreaming discontinues the waking self. Dreaming is an exercise in the acknowledgment of the ways of being outside ourselves, ways of observing ourselves looking out, of witnessing the outsiders that we ourselves are from the inside. There in the dream, where we don’t lie, our uneasy foreignness to ourselves and to others can be its most brazen, can give us back to ourselves, can give us our Comebacks. As Algerians living in France, both Derrida and Cixous shared an uneasy relationship to what they have called their foreignness, but they shared as well the warning that it is not such a simple thing to share a foreign difference. Writing about Derrida, Cixous sees the distinctive “no” of the philosopher as his means of making something of the “notsosimplicity” of the foreign shores both outside and inside the human, sometimes mingling, sometimes mixing together. The notsosimplicity of the dream is that our foreign shores are always crossable there, mixable, and that our most human elements are recognizable nonetheless. Cixous knows Derrida for a mouse in her dream, immediately, and as a footballer, laughing like Medusa. The dream visits can both reassure and provoke our worries over otherness. Outsiders mingle in dreams, exchanging sides, for a time. Cixous’ dream bears a certain resemblance to the scene in which she and Derrida met in the first place. “Right away we reassured each other,” she recalls in The Insister, “we recognized one another in anxiety and in foreignness. Thought thinks only by becoming foreign to itself, by losing consciousness. Right away we worried each other.” These thoughts are akin in feeling the scene of her dream of Derrida. Right away she is both worried and reassured. In his foreignness and in her anxiety is where their thinking together begins. Her dream repeats this wish to think together: worrying over the foreignness that reassures and reassured by the foreignness that worries.

Cixous insists that where dreams are concerned one has to leave the self, walk through the self toward the dark of one’s own night. She concludes that in order to go from one place to another, we must first simply leave. Perhaps this is the invariable lesson of the dream: something is left behind, lost, and furthermore, we, too, have to leave—and sometimes it is ourselves we depart from. The self, after all, is also its interruptions, and then also what we make of them. Cixous’ dream signs her text and gives us the proposition that making something from the dream and from its interruption of our waking self makes a difference.

Photograph Sophie Bassouls, February 26, 2003 © Sophie Bassouls

For Cixous, dreaming is leaving so as to go toward “foreign lands,” toward our own “inner foreign country.” The self’s denial of its foreignness to itself is the lie the dream refuses to tell. Our differences from ourselves are housed in the dream, and so too is the foreign other, that benevolent adversary, since, in the last analysis, we sometimes find ourselves dreaming from both sides. The dream returns us to our departures— French and Algerian shores—to those secret missions of leaving home behind. The dream escapes the lie given the dreaming woman by the awakened philosopher: the lie that we are always all there, all on one side, one shore. And so the dream answers the philosopher, confabulating with the unconscious: you are there, indeed, all of you, you and the others, the mice, there on both sides of the nowhere of your inner foreign country.

Cixous dreams of Derrida so as to speak to him and cross over into his anxious foreign country. Notice: the dreaming woman is on your side, she writes. Cixous dreams of Derrida so as to write, for it has always been a question of writing, between them, of “living in language,” she says. Cixous dreams of Derrida to keep him living in language, on her side. The inner foreign country of the dream is that other thinking Derrida had been after for so long, foreign to himself in dreams, and in Cixous’ dreams as well. “We met each other in order to think in language,” Cixous asserts. And they meet again, for the same reason, in her dream.

Noel Glover is an Addiction and Mental Health Worker with the South Riverdale Comminty Health Centre. He holds a PhD from the Faculty of Education at York University in Toronto. His research draws from psychoanalytic theories of human development and paradoxes of lived experience for the development of pedagogy.

"Dreaming woman is on your side" © February 2017