Do Monster's Dream?

In May 1947 Jorge Luis Borges—Argentinian poet, writer, librarian, and dreamer—published a story about a monster named Asterion. It is a tale that turns on a dream. Almost the entire story is told in the voice of the monster, more commonly known as the Minotaur, a creature from Greek mythology that is half bull, half man.

Asterion begins by explaining to readers that he has been terribly misunderstood: “I know that I am accused of arrogance and perhaps of misanthropy, and perhaps even of madness. These accusations (which I shall punish in due time) are ludicrous." Then he tells the reader about his house and a dream:

The house is as big as the world—or rather, it is the world. Nevertheless, by making my way through every single courtyard with its wellhead and every single dusty gallery of gray stone, I have come out into the street and seen the temple of the Axes and the sea.

That sight, I did not understand until a night vision revealed to me that there are also fourteen (an infinite number of) seas and temples. Everything exists many times, fourteen times, but there are two things in the world that apparently exist but once—on high, the intricate sun, and below, Asterion. Perhaps I have created the stars and the sun and this huge house, and no longer remember it.

Asterion tells us that his house—the famous labyrinth constructed by Daedalus—is anything but palatial, despite the fact that he is the offspring of a queen. Nor is it a prison. He is free to come and go, and he once walked out into the streets, but retreated back into his subterranean home upon hearing people's cries of terror at the sight of him. It was this venture into the streets to which he refers in the passage above, the one he didn't fully understood until he dreamt about it.

Asterion tells not only his dream, but also of his games and an imaginary friend:

Sometimes I run like a charging ram through the halls of stone until I tumble dizzily to ground; sometimes I crouch in the shadow of a wellhead or at a corner in one of the corridors and pretend I am being hunted. There are rooftops from which I can hurl myself until I am bloody .... But of all the games, the one I like best is pretending that there is another Asterion. I pretend that he has come to visit me, and I show him around the house.

Near the end, we find out that the Minotaur is waiting for redemption. He has been told by one of his victims that his redeemer will come one day:

Since then, there has been no pain for me in solitude, because I know that my redeemer lives, and in the end he will rise and stand above the dust. If my ear could hear every sound in the world, I would hear his footsteps.

There are many possible interpretations of this little story, its monster, and its dream. The Minotaur, who has been a mythical Other throughout history, is presented to the reader as a dreaming, imaginative, and desperately lonely creature. Borges compels his readers to see the world through the Minotaur's eyes. Most readers (unless they know from Apollodorus that Asterion is the Minotaur) won't know who the narrator is or what we are seeing until the very end, at which point Theseus speaks and we understand that he has slain the monster:

'Can you believe it, Ariadne?' said Theseus. 'The Minotaur scarcely defended itself.'

The reader can't help feeling surprised and (perhaps ashamed) when she realizes she has been tricked, not only by Borges, but also by the history of “Western civilization.” We have believed a particular narrative for centuries and rarely question the horribleness of the Minotaur.

It has probably never occurred to most readers that the Minotaur dreams.

The dream in this story, referred to as a “night vision,” is easily overlooked. Given that Borges very explicitly describes dreams in nearly all of his stories, often at length, it is comparatively easy to miss this one. One could even speculate that it isn’t a dream at all. But this subtle reference is arguably the very substance that gives this story its shape, as it is in this night vision that Asterion discovers a truth of himself, and we, as readers, enter more fully into his world. Entering into the other’s imaginary almost always brings a reader closer to a character.

An invitation to enter a monster’s dream is a request to sympathize with a terrible creature, share in his fears, his desires, in what he knows, and what he feels. How can we not begin to feel the pain and sorrow he experiences, having no one with which to share his life, and knowing himself to be terrifying in the eyes of others?

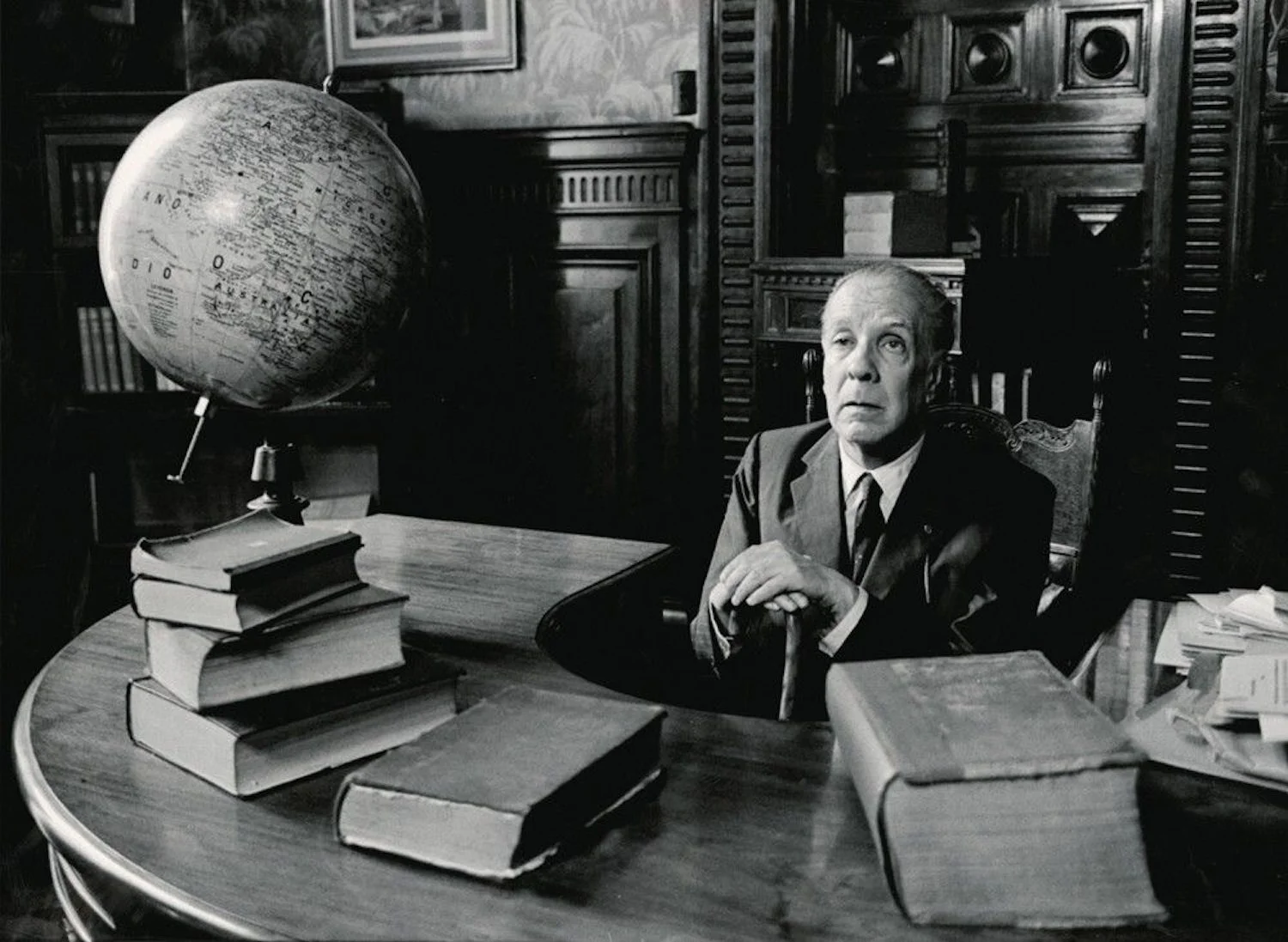

Jorge Luis Borges, Palermo, Sicily, 1984. Photo © Ferdinando Scianna/Magnum Photos

Illustration by Francisco Galarraga

Labyrinth mosaic discovered in the floor of a Roman villa at the Loigerfelder near Salzburg, Austria in 1815. The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna

In his 2003 set of lectures, The Animal That Therefore I Am, Jacques Derrida tells us that it is the dream that challenges any idea of an essential gap between the human and the beast:

I am dreaming through the dream of the animal and dreaming of the scene I could create here.

Asterion is pitiful and heroic; helpless and powerful; blind and keenly perceptive; frightful and endearing; beastly and human; trapped and free. If not for his imaginary friend, he would be entirely alone.

Reading “The House of Asterion” alongside Borges' biography we gather an abundance of meaning. Over his lifetime, through stories of his childhood memories and dreams, Borges supplied his readers with the thread that leads to the center of his labyrinth, and there we discover that the Minotaur is, in fact, his double.

Jorge Luis Borges in the Biblioteca Nacional, 1971. Photographer: Eduardo Comesaña, courtesy of The National Museum of Fine Arts of Argentina

Thirty years after publishing “The House of Asterion,” Borges offered up its source material in a 1977 lecture on nightmares delivered at the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires.

Let us into the nightmare, into nightmares. Mine are always the same. I have two nightmares which often become confused with one another. I have the nightmare of the labyrinth, which comes, in part, from a steel engraving I saw in a French book when I was a child. In this engraving were the Seven Wonders of the World, among them the labyrinth of Crete. The labyrinth was a great amphitheater, a very high amphitheater (and this was apparent because it was higher than the cypresses and the men outside it). In this closed structure—ominously closed—there were cracks. I believed when I was a child (or I now believe I believed) that if one had a magnifying glass powerful enough, one could look through the cracks and see the Minotaur in the terrible center of the labyrinth.

My other nightmare is that of the mirror. The two are not distinct, as it only takes two facing mirrors to construct a labyrinth. I remember seeing, in the house of Dora de Alvear in the Begrano district, a circular room whose walls and doors were mirrored, so that whoever entered the room found himself at the center of a truly infinite labyrinth.

The French book that contained the engraving of the labyrinth was from his father's library. In 1969 Borges said in an interview that he was so frightened of the image that he couldn’t bear its presence. His mother had noticed that he took great interest in the book and suggested he keep it in his room, but he insisted it stay in the library because he was afraid the Minotaur might escape the pages.

One cannot overlook the fact that the labyrinth of Crete is not actually among the “seven wonders of the world,” and so Borges’s memory isn’t to be trusted. At the same time, the imagery and his associations are telling. The memory takes on a dreamlike quality, enriched and made strange, perhaps by the hands of time, or perhaps because the child’s mind invented a particular scene, or perhaps these various occurrences were combined into one.

(I must confess, I have an almost identical story. As a child, around the age of eight, my father purchased a set of “Charlie Brown” encyclopedias for me. One volume featured reptiles, and I was so terrified of one of the images of a snake that I could not bear to be in the presence of the book. In my mind the image was so realistic that it might leap out of the page and devour me. I made my father hide it away. He put it in his bedroom, and that way I could pretend the image did not exist. Remarkably, only a few months ago I discovered the same volume for sale at a used book store. I purchased it, brought it home, and had a good laugh. It turns out that the picture that tormented me was hardly realistic. It was a drawing, and although it was a bit scary, the image certainly did not match the one in my memory.)

Around the same time Borges worked on the story of Asterion he also wrote “La fiesta del Monstruo” (“The Monster's Feast”). In the latter story, he alludes to Juan Domingo Perón, the three-time president of Argentina, as a monster.

The Perón regime affected Borges personally. In the 1940s, Perónism reached its most frightening heights. During this period, Borges’s father died. These were the years in which he wrote his beautiful and nightmarish short story, “The Library of Babel.” Both before and during WWII, Borges regularly published essays attacking the Nazi Party and its racist ideology. By 1946, Borges had lost his position as librarian at the Miguel Cané public library. In retaliation for his anti-Perónism and for siding with the Allies during the war, he was demoted to inspector of poultry, rabbits, and eggs. He began lecturing to earn a living. 1946 was also the year that he wrote “The House of Asterion.”

Interpretations of the myth of the Minotaur abound, but it seems most appropriate to turn to Borges’ own encyclopedic entry in The Book of Imaginary Beings to understand his portrayal of the creature.

The idea of a house built so that people could become lost in it is perhaps more unusual than that of a man with a bull’s head, but both ideas go well together and the image of the labyrinth fits with the image of the Minotaur. It is equally fitting that in the center of a monstrous house there be a monstrous inhabitant.

The Minotaur, half bull and half man, was born of the furious passion of Pasiphae, Queen of Crete, for a white bull that Neptune brought out of the sea. Daedalus, who invented the artifice that carried the Queen’s unnatural desires to gratification, built the labyrinth destined to confine and keep hidden her monstrous son. The Minotaur fed on human flesh and for its nourishment the King of Crete imposed on the city of Athens a yearly tribute of seven young men and seven maidens. Theseus resolved to deliver his country from this burden when it fell to his lot to be sacrificed to the Minotaur’s hunger. Ariadne, the King’s daughter, gave him a thread so that he could trace his way out of the windings of the labyrinth’s corridors; the hero killed the Minotaur and was able to escape from the maze….

The worship of the bull and of the two-headed ax (whose name was labrys and may have been at the root of the word labyrinth) was typical of pre- Hellenic religions, which held sacred bullfights. Human forms with bull heads figured, to judge by wall paintings, in the demonology of Crete. Most likely the Greek fable of the Minotaur is a late and clumsy version of far older myths, the shadow of other dreams still more full of horror.

What are monsters really? And do they dream? If they dream, what do their dreams do? Borges would say dreams dream other dreams, and his stories come out of his dreams. In Borges’s mind, “literature is naught but guided dreaming.”

In the story of Asterion, dreaming is also a memory practice. Borges has retained his dream and shared his truth—this dream from childhood that guarded and announced his fears. He archived that dream in the history of his self, the history of place and time, and wrote it into his fictions. It is a dream of the horrors of buried truths.

The Minotaur dream from Borges’ childhood reappears in the 1975 memorial to H.P. Lovecraft, “There are More Things,” which first appeared in the short story volume, The Book of Sand. At that time Borges no longer worked in the library, and had been living without sight for decades. He was nearing the end of his life. This is another story of a monster, and read alongside “The House of Asterion,” it seems almost like a continuation, or perhaps a conclusion. In it, a man dreams that he is confronted with a dreaming monstrous being in a strange house. The scene recalls Borges’s childhood memory, in which he encounters the image of the Minotaur in the pages of a book.

Toward sunrise I dreamed of an engraving in the style of Piranesi, one I’d never seen before or perhaps had seen and forgotten—an engraving of a kind of labyrinth. It was a stone amphitheater with a border of cypresses, but its wall stood taller than the tops of the trees. There were no doors or windows, but it was pierced by an infinite series of narrow vertical slits. I was using a magnifying glass to try to find the Minotaur. At last I saw it. It was the monster of a monster; it looked less like a bull than like a buffalo, and its human body was lying on the ground. It seemed to be asleep, and dreaming—but dreaming of what, or of whom?

One interpretation of the story is that the narrator is confronted by his double; Borges reflecting upon the uncanniness of his own existence. Some of the passages in this story are nearly identical to ones in the “House of Asterion.” He asks explicitly what it must be like to be the monster and what is was like to occupy the strange house. In an allusion to the Minotaur's unlocked prison, he writes: “I conjectured that it hadn't locked the front door and the gate because it hadn't known how.” Of the house and its surroundings, the narrator notes that as a boy he realized these things, “only by reason of their coexistence are called ‘the universe,’” recalling the 1947 sentence: “The house is as big as the world—or rather, it is the world.” As one biographer tells us, “Borges realized that the center of the universe is experienced at any moment in any place”

A monster's lair is the center of the universe in both of these stories. Indeed, this might refer to Buenos Aires, which became increasingly unfamiliar to its inhabitants over time; it may be Borges's house, which he occupied with his mother until she passed; it may be his mind, its memories and dreams, and its strange, seemingly inescapable labyrinthine passageways whose key remained undiscovered to the aged man.

Borges reported in a 1967 interview with Richard Burgin that he wrote “The House of Asterion” in a single day. He also revealed some of its meaning:

I felt there might be something true in the idea of a monster wanting to be killed, needing to be killed, no? Knowing itself masterless. I mean, he knew all the time there was something awful about him, so he must have felt thankful to the hero who killed him.

He suggested in that same interview that Hitler knew his whole scheme was preposterous and “in his heart of hearts he really wanted defeat.” This was a repetition of a 1944 essay, in which he wrote: “To be a Nazi...is a mental and moral impossibility; it's unreal, uninhabitable. You can only die for it, lie for it, kill and spill blood for it.”

Hitler quiere ser derrotado.

Hitler wanted to be defeated.

Borges went so far as to speculate that Hitler unconsciously collaborated with the very entities that would annihilate him—the vultures and dragons “who should not have been unaware that they were monsters.” This seems to have been a preoccupation for him for years, one that troubled him on various levels, and one that would be repeated over and over in his stories and poetry, interviews and lectures.

The book in Borges's father's library provided the imagery for the recurring nightmare, as well as a setting in which to narrate his own fears. One wonders what might have been so frightful about that image to a young Borges—was he already aware of his own monstrousness? Did he feel trapped in his parents’ house? Could he foresee that he would live most of his years in darkness? Whatever it was that struck fear into Borges's heart seemed to stay with him for the duration of his life. The labyrinth and the Minotaur anchor the storylines that present Borges’s double: the labyrinth as his house—a trap that isn't a trap—and the Minotaur, a monster, alone in the darkness.

Reports of Borges’s relationships with his mother, father, and lovers vary in their interpretations. But certain things are generally agreed upon: his mother had tremendous influence over him. He lived with her until she died and she cared for him as his blindness became increasingly debilitating. His father was an overbearing man. One particularly traumatic life experience occurred when his father brought the young Jorge Luis to a brothel, where he was expected to have sex with the father’s mistress. It seems his parents, and certain circumstances and events shaped his sexuality. It is widely reported that Borges’s discomfort with sex affected his relationships in adulthood.

A passage in the story “Emma Zunz” is believed to be a reference to Borges's own sense of the sexual act as an act of violence perpetrated by men toward women:

She thought (and could not help thinking) that her father had done to her mother the horrible thing being done to her now.

It may be that his own monstrousness had something to do with the horror of realizing his father (a bull?) had penetrated his mother (the queen?). It is surely no coincidence that the story was inspired by George Frederick Watts’s 1885 painting, The Minotaur, which was created to depict male bestiality and lust in an era of social purity campaigns.

Sigmund Freud’s essay on "the uncanny" seems relevant here. For Freud, this special sense of dread and anxiety is tied to blindness and driven by the threat of castration: “A study of dreams, phantasies and myths has taught us that a morbid anxiety connected with the eyes and with going blind is often a substitute for the dread of castration.” Freud asserted that the figure of the “double” was “insurance against destruction" of the ego. It may be the case that fiction, poetry, and dreamwork were all ways for Borges to confront his own fragility. As Freud writes, “This invention of doubling as a preservation against extinction has its counterpart in the language of dreams.”

Doubles are everywhere in “The House of Asterion”. The Minotaur's house is referred to as the temple of axes, which refers to the labrys—the double ax that has come to symbolize Minoan culture. Any number of figures might serve as the monster's double: Borges himself, of course, but also Hitler, Perón, Theseus, and perhaps even the reader herself.

“The House of Asterion” demands much of its readers. If we are to read the Minotaur as Borges’s double, and if we take Borges at his word, we are asked to identify with monsters. And perhaps we are also asked to recognize the monstrousness that inhabits the human condition.

—Melissa Adler is an assistant professor at Western University in Canada. She is the author of Cruising the Library: Perversities in the Organization of Knowledge (2017).

"Do Monsters Dream?" © December 2017

Pasiphaë and the Minotaur. Attic-red figure kylix. 340-320 B.C. Bibliothèque nationale de France

George Frederic Watts, The Minotaur, 1885, Photo © Tate Museum CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)