Dancing with a Great Dane

By IAN BALFOUR

Theodor W. Adorno, Dream Notes, Cambridge: Polity, 2007

When was the last time you dreamt of showing up at a party that Trotsky was at? And have you ever dreamt about Fritz Lang after having lunched with him earlier in the day? Are a lot of your dreams about brothels? If not, you are probably not Theodor Adorno, whose posthumously published dream "protocols" record some of the singular dream experiences of this extraordinary thinker and writer. But you could compare notes.

Dream Notes reproduces numerous short accounts (some a few pages, some just two lines) of dreams Adorno had, many of them from his period of exile in Los Angeles, many in the shadow of WWII. His practice was to try to record his dreams as such, virtually without interpretation or supplementary commentary and with no significant after-the-fact changes. He seems largely to have succeeded in doing so, though we cannot know for sure. The dreams are not all highly charged, much less profound. Adorno is content at times to present banalities simply because they occurred. But, thankfully for us, this exceedingly compelling thinker sometimes had downright interesting dreams and provocative accounts of them—interesting in themselves and for their resonance with Adorno’s waking life of intense thinking, writing, moving about and acting in society.

Adorno was primed by his early engagement with psychoanalysis to be interested in dreams. His interest was philosophical and practical, with one eye on what they said about human selves, subjectivity, and their challenges to inherited notions of the self, and another eye on how things might be improved by attention to all the dynamics that Freud and company uncovered, many of which—but especially repression—would become pivotal for the Frankfurt School. The centrality of the dream has faded for psychoanalysis, given advances in awareness of so many other manifestations of the unconscious and of the wealth of materials just at the level of consciousness as such. But the dream continues to fascinate, and some dreams more than others.

Here, as a tease and a touchstone, is one of the more spectacular entries jotted down in Adorno’s dream-book:

I had been invited by the headmaster of my high school, which is now called the Freiherr vom Stein-Schule, to contribute something to a Festschrift in honour of its fiftieth anniversary. Dream: a ceremony in which I had been solemnly installed as head of music of the high school. The repulsive old music teacher, Herr Weber, together with the music teacher, danced attendance on me. After that there was a great celebratory ball. I danced with a giant yellowish-brown Great Dane—as a child such a dog had been of great importance in my life. He walked on his hind legs and wore an evening dress, I submitted entirely to the dog and, as a man with no gift for dancing, I had the feeling that I was able to dance for the first time in my life, secure and without inhibition. Occasionally we kissed, the dog and I. Woke up feeling extremely satisfied.

Sometimes Adorno wakes up in shock, sometimes laughing. The extreme satisfaction expressed here is probably the most positive moment of anything recorded in any of the dreams. All the problems of daily life and the horrors of current world history have receded and for a change Adorno can live a non-self-conscious life, dancing gracefully (the very sign of anti-self-consciousness in Kleist’s great “Marionette Theater” essay). A few moments of freedom emerge from the often crushing un-freedom from the administered, damaged life. These are available only in the dream, but they provide pleasure on the far side of the dream and perhaps prompt a little thinking.

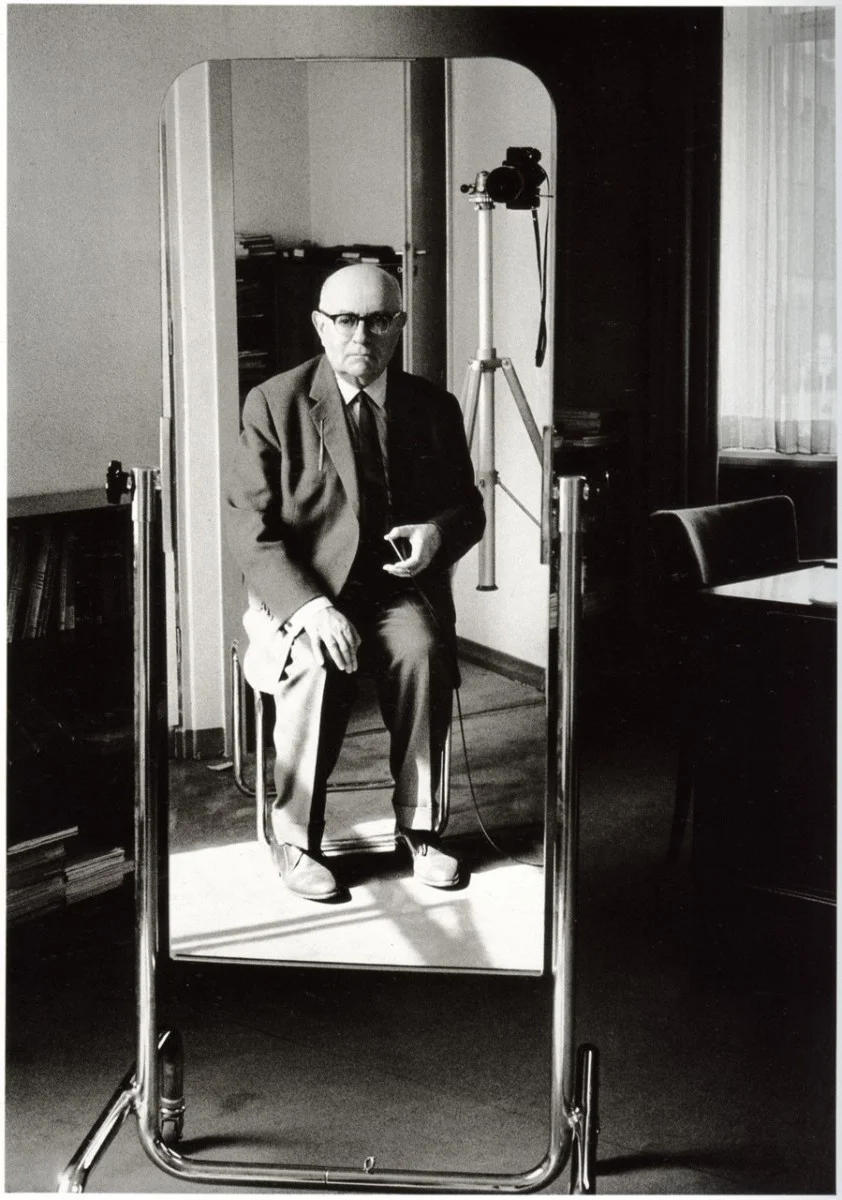

Theodor Adorno © picture-alliance/dpa

“In dreams begin responsibilities,” Delmore Schwartz’s dictum goes and certainly Adorno’s recorded dreams are shot through with a sometimes burdensome sense of responsibilities and duties: essays to write, meetings to attend, and quite a few tests to take (long after he was an established professor and a highly regarded intellectual). Adorno’s dream-life informs a good deal of his super ego, not least while asleep. It’s not exactly the Protestant work-ethic working overtime, but a huge sense of responsibility looms, including that of the most pressing sort, or skewed versions of real responsibilities, as in the face of Hitler’s Germany, both painfully and happily experienced by Adorno from abroad. So many things to do and to suffer, so much anxiety attached to them.

But in Adorno’s dreams begin also ir-responsibilities, sometimes accompanied by a sense of helplessness. Among these ir-responsibilities, the most prominent is a kind of sexual abandon that exceeds, if gossip and the occasional fact are to be credited, Adorno’s libertine proclivities that he acted upon in his daily and nightly life. Thus: many trips to brothels, kissing of boys, and quasi-erotic relationships with animals turn up in these dreams. Sometimes the abandon and responsibility impinge on each other, as when Teddy, the dreamer, is accompanied to a brothel by his wife and mother, without anything seeming terribly amiss. And yet for all this, the act of sexual intercourse in a dream is never recounted or, as far as we know, experienced.

Dreams come unbidden: we are not at all free to dream them or not. And once in motion, with the minor exceptions of lucid dreaming and some pockets of the possibility of the dreamer exercising her or his will, we are the ‘subjects’ of our dreams in that we are subject to them. Adorno wrote in Minima Moralia: “Between ‘a dream came to me’ [es träumte mir] and ‘I dreamt’ lie the ages of the world. But which is the more true? No more than it is spirits who send a dream, is it the ‘I’ that dreams.” In a good many dreams, we are so much freer than in daily life, far less inhibited by societal mores and the laws of nature. Still, the materials of dreams are not of our own making or choosing, as Marx said of the circumstances of history. As an involute of freedom and un-freedom, the dream performs something of the negative dialectic that drives life—and death. (Adorno proclaims: “dreams are as black as death”). Perhaps in exile, wish fulfillment may have been an even more pressing concern, consciously and unconsciously, than otherwise.

Theodor Adorno, Selbstportrait, 1963 © Stefan Moses

Might it be said of dreams what Benjamin maintained, in his Moscow Diary, of facts: that they are “already theory”? Yes and no. “No” because there is something irreducibly singular about the dream: it is one’s dream on a particular day and time and no one else’s. Even the so-called recurring dream or quasi-recurring dream (as in Adorno’s multiple dreams of execution and even crucifixion!) is marked by its own singularity of a sort, as a repetition, as a dream that has occurred before. But “Yes,” in part because dreams so often seem to be allegorical or at least to point beyond their surface, and often we have a sense that we can learn something from them, even if they successfully elude the interpretability Freud dreamed of early on. Moreover, in Adorno’s case, the dreams can serve as mini-exemplars, brief allegories of his philosophy of non-identity. Adorno often notes a much-attested feature of dreams, namely, that a certain thing or person or entity both is and is not what we normally think of it as being, as when the Vienna he visits in a profoundly affecting dream about the death of Alban Berg (which first made Adorno realize the magnitude of his loss, even though he had been feeling the loss for a good while) both is and is not the city most people would objectively recognize. The wavering, ambiguous status of dream-entities thus can stand as one emblem of the principle of non-identity, requiring not an elaborate Hegelian argument in its favour, but only the striking lyric moments of the dream-work that hardly seems like much work: the "leisure of the negative," as it were.

Dreams, we can glean from Adorno, present us with more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophies. A philosophy that cannot dream, and respond to dreams, would be an impoverished sort of thinking.

Ian Balfour is professor emeritus of English at York University. This is a revised version of his review essay, "Adorno’s Non-Waking Life," first published in Reviews in Cultural Theory, Issue 1.1 (May 1, 2010).