Once I dreamed I fell from a ship.

–Fatima

And so begins Fatima’s memory of a dream recalled in a single sentence: “Once I dreamed I fell from a ship and then I woke up…and was afraid.” Her words are reminiscent of any child awoken by a terror that arrives in the dead of night. She adds: “then I couldn’t sleep anymore.” Plucked out of the memory of traumatic experience, and composed by the violence of war, Fatima’s dream conveys a haunting reality that leaves her sleepless and afraid in waking life.

The sentence holding the contents of a dream is unravelled in a short film entitled Fatima’s drawings by photojournalist Magnus Wennman. The film gently follows a child’s memory of a war that she is made to endure by accident of birth, at this time, in this world, in a country called Syria. Raging on for six years, war has become the normative grounds of existence for millions of children like Fatima. Through no fault of their own these ordinary children are born and raised in hostile conditions of adult carnage and cruelty.

Five boys from Promahi in front of the refugee ship S.S. Samos that evacuated children during the Civil War in Greece. © David Seymour / Magnum Photos

As world spectators to the mass degradation and killing of children, we have met these small people in photographs of dead and dying bodies beached on shores, bombed in schoolyards, burned and maimed by flying shrapnel. Such images are a constant reminder of the brutal and unrelenting killing spree waged on the lives of millions of Syrians. If these images shock and dismay the world community, its international citizens remain unable to collectively act in the social interest and protection of other people’s children.

In the wake of World War II, photographs of children affected by war, famine, and environmental ruin have become an aesthetic genre of its own. Into this blur of visual images composed of children’s lives arrives the aesthetic interventions and photo-activism of Wennman. From a young age, the Swedish photographer was compelled to document stories of children living in and through unbearable circumstances. Fatima’s dream, captured movingly in film, is one testimony Wennman visually puts forth on behalf of children in Syria and other nations plagued by war, mass degradation, occupation, and ethnic conflict throughout the world.

Wennman’s critically acclaimed photo essay, "Where the Children Sleep" is prelude and accompaniment to this film. Fatima is one of many children who appear in this startling visual essay imaging children in various states and places of rest and unrest. His photographs of children searching for sleep from the brutality of war gives an intimate, shocking glimpse of the unlivable conditions of people fleeing homelands. It offers a view of bare family life in times of societal ruin. Wennman shoots scenes of children sleeping in woods, boats, detainment centers, and strangers’ homes in order to give viewers as sense of what life might be like for children and families desperately eking out a place of refuge at mostly unwelcome borders of distant and not so distant nations.

In their parent’s harried, frantic search for safe havens, Wennman finds children are given to sleep in inhospitable places that seem unlikely for dreaming. And yet, despite, or indeed, perhaps in spite of these intolerable conditions, children do dream. The series depicts searing images of Syrian children at sleep and not being able to sleep. In a caption to each photo, children and their guardians give words to the dream-like qualities of their disturbed slumber. We learn of dreams of peace, of soccer balls and lost toys, and of dead parents rising like a phoenix to rescue children from their interminable plights. We are privy to unforgettable images of children’s eyes shocked to the core of their being, wide open and wounded, cowering in the fetal position. We are surprised by the seemingly unusual strength of some children like Maha who defiantly informs Wennman: "I do not dream and I'm not afraid of anything anymore."

Maha, 5 years old, Debaga, Iraq. Maha and her family fled from the village Hawiga outside Mosul seven days prior. The fear of Isis and the lack of food forced them to leave their home, her mother says. Now Maha lays on a dirty mattress in the overcrowded transit center in Debaga refugee camp. ”I do not dream and I’m not afraid of anything anymore”, Maha says quietly, while her mother’s hand strokes her hair. © Magnus Wennman

Fatima, 9 years old, Norberg, Sweden. Together with her mother, Malaki, and her two siblings, Fatima fled from the city Idlib. After two years in a refugee camp in Lebanon, the situation became unbearable and they made it to Libya where they boarded an overcrowded boat. On the deck of the boat, a very pregnant woman gave birth to her baby after twelve hours in the scorching sun. The baby was a stillbirth and was thrown overboard. Fatima saw everything. When the refugee’s boat started to take on water, they were picked up by the Italian coastguard. © Magnus Wennman

Fatima’s experience of not sleeping in the wake of a bad dream is uncovered in this series. The dream she relays to Wennman carries contents he cannot let go. Subsequently, her dream takes center stage in the photographer’s short film.

In Fatima's Drawings, we first meet the small girl child, alone in her narrow bed, trying to sleep. As she lays motionless and holding a teddy bear she recounts the contents of the dream that evidently haunts her still. The blue-black, grainy quality of the film provides a stark, impoverished setting for Fatima’s equally sparse and colourless visual narration of events. Her telling of what happened to her in a boat echoes the desolate and toneless fear she expresses on waking from the dream. “I was afraid,” she remembers, eyes unblinking, still gripped by the image of her tiny self falling from a ship to the sea, falling out of existence into the throes of certain death. The mortal fear the dream brings vanishes in the light of day and yet, these feelings silently drive the composition of her drawings of trauma that bear witness to terrible events her family experienced during their frantic, forced exile from Syria.

The effect of Fatima’s telling is heightened by Wennman’s cinematographic attention to tiny details in her drawings and narration. In her book, Dreaming in Dark Times, Sharon Sliwinski says that we might understand the dream “as an intersubjective event that requires animation—a special orchestration of voice and breath.” Using film, Wennmen stunningly embarks on this orchestration of memory, voice, breath, and image to lift up the affective qualities of Fatima’s dream. As Fatima tells the tale, Wennman, with the collaboration of animator, Jenny Svenberg Bunnell, uncannily brings the small details of Fatima’s drawing tremulously to life. The details in the drawing, child psychoanalyst Melanie Klein reminds us, is evidence of the unconscious at work in its articulation of traumatic experience. Or as jury member for the film, Duy Linh Tu puts it: “The strength [of the film] was really just the creativity and the way of querying into and demonstrating something that we really can’t see…we can’t see thoughts.” Although minimal, Wennman’s aesthetic intrusion on Fatima’s drawings helps us to see her thinking and feeling, to make Fatima’s memory “move a bit,” as he says.

We watch spellbound as the girl’s pencil drawings begin to move: a bomb drops, a baby falls, a boat drifts, and the sun fades. The aesthetic effect of Fatima’s moving memory plunges the viewer into a scene that feels like the heady work of a child’s dream. The film’s emphasis on the emotional labor of Fatima’s narration, in deep breaths, audible sighs, sad eyes, and stark pauses, amplifies the silent, visual, roaring affects of her memory. Wennman’s attention to miniature sounds, words, and images conveys the multimodal effect of dreaming as the significance of Fatima’s story is brought home to the viewer in bits and pieces of meaning, feeling, and symbol. This is a film that compels a second and third viewing to gain a sense of the overwhelmed qualities of meaning a traumatic dream falters to say.

Through visual testimony, Fatima recounts the terror propelling her family’s desperate flee from atrocities that fell on the inhabitants of Idlib. She uses simple, realistic drawings accompanied by bare factual narrative to tell the tale. The drawings are typical of any child at Fatima’s stage of development in that they provide a figurative version of her experience. The figures of people and places are not aesthetically unique: they resemble realistic images of war composed by children of a similar in age from all walks of life. The narrative is equally as straightforward. As Fatima speaks of what happened to her before and after the family fled the war in Syria the film manipulates small details of her drawings in accordance with her testimony. Taken together the drawings and oral testimony provide a vivid report of Fatima’s memory of violent exile.

The film is set in the present, in the ordinary, day-to-day activities of children living everywhere. Although she has experienced the unthinkable, life in the newly found refuge bears little trace of her trauma. Routine scenes of family life carry Fatima through the film. We see a child at the breakfast table, in the classroom, at the bus stop. Fatima’s every day activities resemble those of any school child.

Though we cannot see it, Fatima is a child indelibly marked by the violence of war. Yet, one symbolic activity of childhood betrays the horror of Fatima’s inner life—the act of drawing. After the war Fatima is driven to draw. She cannot stop drawing. Spectators of Wennman’s film hear pencils rub against the paper as she creates her illustrations. We watch riveted as Fatima compulsively draws what happened to her in picture after picture engaging the common visual, symbolic labor of children.

Fatima’s narrative begins to shift and she expresses a wish for her simple life before the devastation of war, when she played happily with a childhood friend, Rana. She illustrates the wish in her drawing of an apartment with swing sets, where children play in the playground as she and Rana swing side by side. As she draws, Fatima is filled with memories of the traumatic past. “I love Syria,” she remembers, “but now it is not good.” The next drawing is a copy of the first but with a difference: Fatima removes the playground and adds details of planes overhead. As bombs fall on her picture of the city and children of Idlib, Fatima’s narrative starts to shift: “It’s very scary. I do not know who they are, but it is not good.” The next drawing skips over the family’s unbearable stay at the camp at Lebanon to their attempts to flee by boat from Libya. The boat, a rubber dingy with sail, is populated with figures of men, women, and children.

The boat—the navel of Fatima’s dream—is also at the center of her visual testimony. Again, as she draws, Fatima verbalizes the scene: “There was a mother who gave birth to a baby,” she recalls. “A boy or a girl, I don’t know.” In the middle of the boat she draws a figure of a man holding a baby. At the edge of the drawing, another man stands over the baby placed against the side of the boat. She continues telling the story: “I watched as two men threw the baby into the sea.” Stunned silence stretches across the film. Small details of the picture begin to slide. Down, down the baby and the sun fall, simultaneously, ominously to the sea as Fatima breaks the silence: “It was the first time I saw something like that. It was not good.” For the third time in the film, the girl uses the phrase: “it was not good.” And then, an after thought when she admits: “I do not like the sea.”

The scene ends with the animated boat rocking gently side to side, abruptly cuts out of the dreamy state of her visual testimony into Fatima’s newly found refuge in the forests of Norburg, which she describes as “a little cold and beautiful.” The film leaves us in the middle of things, with Fatima’s renewed wish “for Rana, to play again.” The protagonist settles back where the film begins, in a bare room on a narrow bed, eyes wide open where, once more the child anticipates a return of the bad dream—images she cannot put to rest.

As we float through Fatima’s fragmented recollection of inchoate traumatic experience, the film’s visual and narrative strategies compel viewers to participate in the blurry meanings her nightmare invokes. With disjointed aesthetics referencing history, reality, testimony, trauma, symbolism, and melancholic dreaming juxtaposed each against the other, memory drifts in and out of broken registers of a child’s interpretive labor. Is the dream real? Fatima herself is unsure as she contemplates its traumatic place in her new life in Sweden, which seems far from harm’s way. And yet in her drawings danger looms, the threat travels with her, lodged deep inside.

Fatima’s witness of a baby tossed to the sea returns in her nightmare of falling from a ship. The trauma of this witness finds symbolic form in the scene of drawing. Fatima has little knowledge of the events that led to the dropping of the baby from the boat. But her strange observation, “It was the first time I saw something like that” jars, interrupts, and even devastates the viewer’s sense of childhood as undeserving of such catastrophe. Fatima’s syntax is void of emotion as she unflinchingly recounts the witness of the dead baby. She speaks the event matter-of-factly, as if she should have known better, as if she expects that babies, like bombs, will fall, as if she is preparing for this certain event to visit again. Although, Fatima makes no explicit connection between her witness of a baby falling to the sea and her own falling in her nightmare, she does offer a muted link between reality and the dream world. As she draws her story to a close, a faint shadow flits across her face, and in an understated and yet rueful tone she confesses: “I do not like the sea.”

The child’s traumatic dream of war is an unlikely source of social and political insight. Its impact is soft, small, and barely visible against the daily bombardment of hard visual and textual evidence of crimes committed against innocent civilians during the Syrian war pouring out of news agencies worldwide. And yet Fatima’s dream silently indicts. The nightmare holds adults accountable without ever directly accusing anyone of wrongdoing. “It was not good,” Fatima’s dream tells us thrice, conveying a great deal about deadly history, war, and its irreparable effects on a childhood, on existence, on a people, on a world.

What might be the social and political impact of the child’s dream if we take it seriously that “war is not good” in the unforgettable way that Fatima articulates? Does the child’s bad dreams compel a proper hearing? Even Freud, the inventor of dream analysis, was reluctant to make too much of the child’s bad dreams triggered by the shock of war, disaster, deprivation, or sexual and physical violence. Bad dreams, Freud claimed, were provoked by repetitive anxiety and ladled with traumatic neurosis. The traumatic experience resists being subjected to the “dream-work.” Something wakes the dreamer before the mind is able to undertake this psychological labor of transfiguring the disturbing events. In his short book, On Dreams, Freud refers to this work as a “safety valve” function for the mind, which is activated when the dream stalls violently, breaking off in midstream, rudely waking the dreamer of her chance of receiving new knowledge or an end. This is the case for Fatima’s dream when she woke up before her tiny body could fall down, down into the bottomless sea.

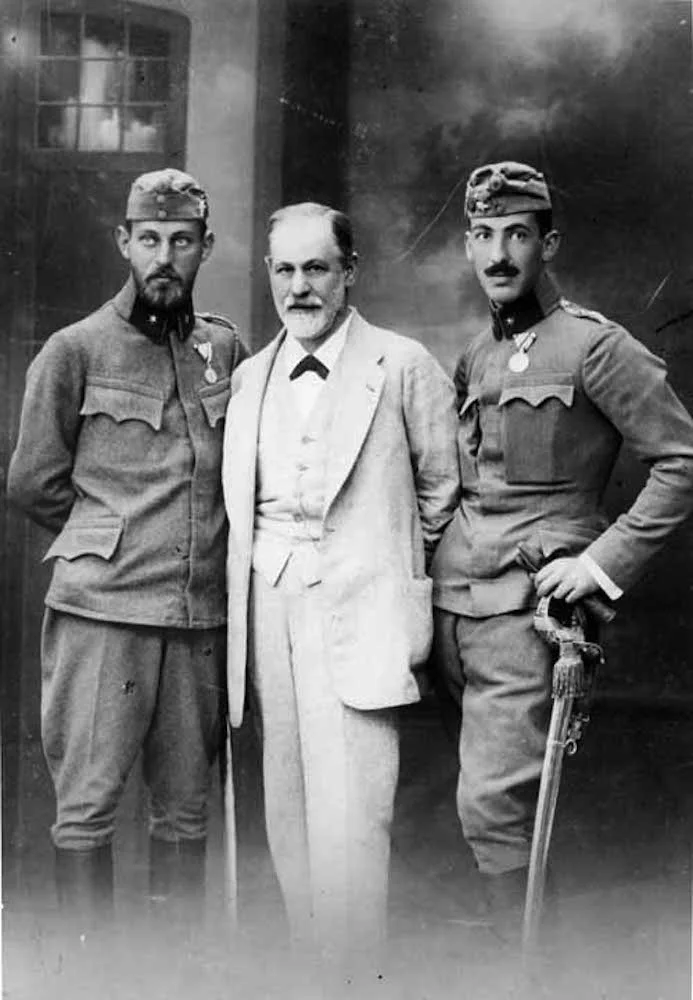

Sigmund Freud posing with his sons Ernst and Martin in military uniform. Austria 1916, cabinet card, Ellinger, vorm Bertel & Pietzner, Library of Congress, Sigmund Freud Collection

Unlike ordinary dreams, Freud came to understand traumatic dreams to be driven by something other than wish fulfillment. Although he did not outright dismiss them, as parents often do, he stripped them of a proper hearing. Freud defined trauma as an incomprehensible shock to the nervous system that is witnessed but cannot be integrated. Having pushed out into the unconscious the contents of our own childhood nightmares, the traumatic dreams of children affected by abuse, disaster and war are too much for the body and mind to take and have little or no recourse to symbolization.

Despite this damaged symbolic functioning, Wennman steadfastly takes into historical account the political significance of children’s dreams, drawings, and testimony in the midst of complete and utter social ruin. He demonstrates that even if unreliable, the unspeakable content of trauma risks symbolic form in fragmented and swirling recurrences and reversions of sleeping and waking images. Speaking the bad dream as she animates and illustrates its content, Fatima provides a faint recourse to the inchoate qualities of traumatic experience. In Wennman’s filmic witness of Fatima’s dream, try as we may, we cannot discount the veracity of its content as it stealthily corresponds with her actual experience. Similarly we cannot wish the bad dream away as it finds her when she is asleep and at play. The dream leaves scary feelings in its wreckage that will not be denied a symbolic hearing. These feelings rise from the dead to disturb the child’s sleep, tapping into mute screaming affects that bolster one’s internal capacity to survive the experience of war. In this sense the traumatic dream is actually vital to the dreamer’s securing a continued existence. Fatima’s dream of falling to the sea survives the threat it delivers to the dreamer; in turn, something in the dream carries Fatima on in her daily life.

Wennman’s cinematic work with the child’s visual testimony harkens back to the earlier studies of war-affected children conducted by child psychoanalysts Melanie Klein and Donald W. Winnicott. In their time, these analysts took it upon themselves to therapeutically respond to the fears and anxieties of British children living through the Second World War. In her pioneering work with the visual testimony of children, Klein found that children expressed the personal and social affects of war trauma in the details of their drawings. In illustrations that uncannily resemble those drawn by Fatima, her child analysand Richard drew his distress with war in realistic images of airplanes flying overhead and bombs falling to the ground.

In a paper called, "The Theory of the Parent-Infant Relationship," Winnicott would later add the discovery that children’s witness of extreme trauma and war was experienced as familiar because children are born with a primal anxiety that adults will do them harm, inwardly fearful that adults will abandon them, leave them to their own sorry devices. Fatima’s offhand remark after narrating the baby’s descent to the sea, “It was the first time I saw something like that,” incorporates what Winnicott describes as the infant’s primal catastrophe of being dropped. For Fatima, witnessing the baby plunge into the sea and dreaming about her own catastrophic falling can be understood as “a confirmation, not a new experience,” to borrow Adam Phillips's words. Fatima intuitively accepts that children are prone to being dropped by adults and adult concerns. For this reason, the psychoanalysts believed the threat of war is close to the inner world of children and that through children they could learn more about the psychosocial apparatus of adult war.

Despite the important news a child’s dream brings to the world, by in large, the adult community refuses to attend to their nightmares of war. Dreams archive children’s experience of traumatic history at the mercy of adults entrusted with their care. A child is dreaming because upon her birth, the world presents to her a threat of the unknown, the feared, the unthinkable, as well as the potential of newness and the possible. Dreaming is the mental mechanism by which we think ourselves into the world of others. Children’s dreams universally relay and prophesize a dire message about their uneasy relation to adults and the external world and their fears that both might present them with harm. Perhaps this is why, for adults, a child’s dreaming is too much to take.

As adults fumble around trying to protect and shield their children from the real contents and consequences of history, killing, mass violence, and destruction, children take war personally. They take on and into themselves, the world’s catastrophes, often with little symbolic space to voice the unimaginable acts they experience, witness, take responsibility for, and hold inside. Children sense that they are the reasons for and targets of adult conflicts and they have no recourse but to dream, to draw, to retreat into silence and the protection of their shaken inner world. For young children, dreams provide a holding place for extreme experiences of abuse and violence and the more horrible contents of the social world. And yet as parents, adults, teachers, and helping professionals we all too often discount the potent content of children’s bad dreams. Perhaps we recognize all too well the grim accusation a child’s nightmares places upon us—the social grievances that cannot be explicated otherwise. As we all were once children with nightmares, we may still be too close to the violent truth of feeling vulnerable at the mercy of grownups in charge of a big scary world.

Children’s dreams—both good and bad—speak chillingly to the evil acts that children imagine adults commit. When children speak of monsters, boogey men, creatures that hide under the bed, these wild things taking hold of their fears are too easily set aside as not real—as just a dream. But what happens when these dreams are not made up, when adults do commit evil acts on or in full witness of children? What becomes of the dream whose content is real—dreams that testify to being snatched from parents, sexually attacked in the night, killed by a stranger, left on a doorstep, bombed by an enemy, or dropped from a boat? Can we afford so easily to dismiss these dreams indexing the worst acts of social and political life? As Fatima’s night vision seems to suggest some dreams are too fantastic to be believed yet too true to be fiction.

Aesthetically Wennman’s film engages in the dream-work of Fatima’s mourning for a dead baby, a dead girl, a dead self, falling out of existence in a world gone mad. The child’s drawing powerfully animates the emotional situation. Wennman compellingly demonstrates that the child’s dream bears witness to the effects of violence on her potential to think, to play, to act, to be. Fatima’s fragment of history is difficult to digest and yet, it is history in the making of a self, indeed, of a world according to Phillips: “Dream work—the process of inner transformation—is the making of history," he writes in Promises, Promises. By providing a social forum for its secret moving parts, Wennman teaches us that we would do well to listen carefully to the child’s dreams. The little film offers insight into war and its affects on the life of children who are subject to unimaginable violence that exceeds the capacity of speech.

In his book, Playing and Reality, Winnicott argues that “If the baby is not held it will fall infinitely.” Wennman’s film bears witness to this nightmare as well as the promise of Fatima’s dream to keep her from falling infinitely into the abyss of a despairing sea. The millions of children currently affected by violence, abuse, neglect, mass degradation, and war is unprecedented. In such times the adult community, the social, and ultimately the maternal environment, drops the child. If most children move beyond this infantile fear, children affected by war are returned to the baby’s unimaginable agony of falling out of time and place, out of their parent’s safe hold and haven and human existence. When children dream of war, the experience carries within it a wish for security, for being held, for care and freedom. If not yet properly political, these latter elements tell us something about the dream’s significance for our understanding of the child’s needs—indeed, of our needs and not only in times of war.

After the carnage in Syria finally ends, its impact will remain in the imaginary life of children like Fatima. Part of our responsibility as adults is to tend to the inner lives of children whose dreams of a peaceful, war-free existence are shattered by the memory of dropped bombs and dead babies. Built from the tiny acts of history, in Wenmann’s stunning rendition, Fatima’s dream exceeds the personal work of mourning. The child’s dream-work enters social and political life as a plea to attend to our primal fears of being dropped out of human existence before and after the bombs fall. These fears that ground the very impulse to war in the first place also provide the means for working through. We need all of our human creativity, all our dreams—good and bad—to put history back into the picture before the bombs cease to drop and after the war comes to an end.

Aparna Mishra Tarc is an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at York University and author of The Literacy of the Other: Renarrating Humanity (2015).

"A Child is Dreaming" © February 2017